Calcified artery. Calcified Arteries: Understanding Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Options

What are calcified arteries. How does arterial calcification develop. What are the risk factors for artery calcification. How is coronary artery calcification diagnosed. What are the treatment options for calcified arteries. Can arterial calcification be reversed. How can you prevent artery calcification.

What Are Calcified Arteries and How Do They Develop?

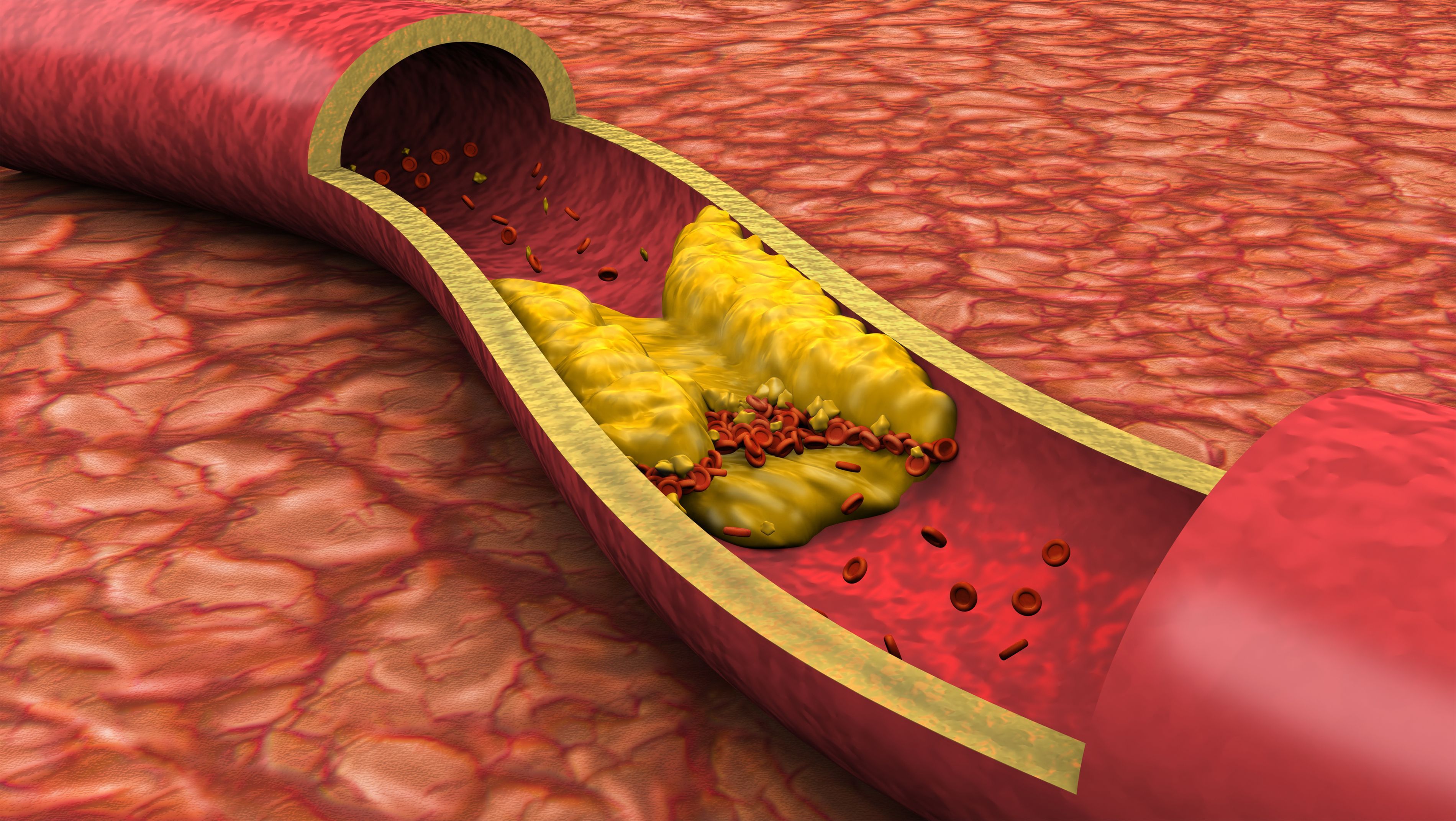

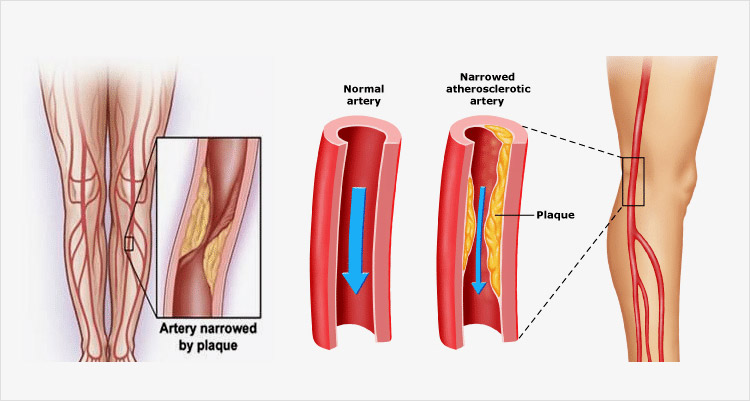

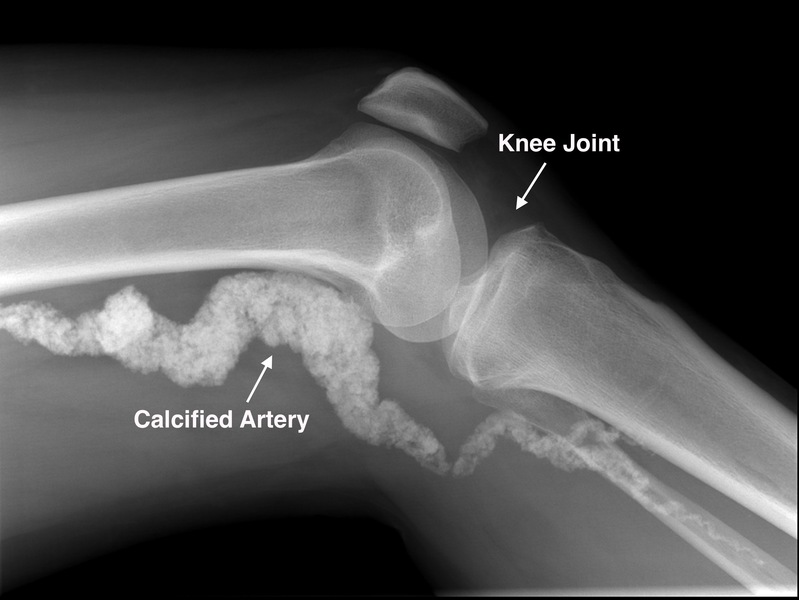

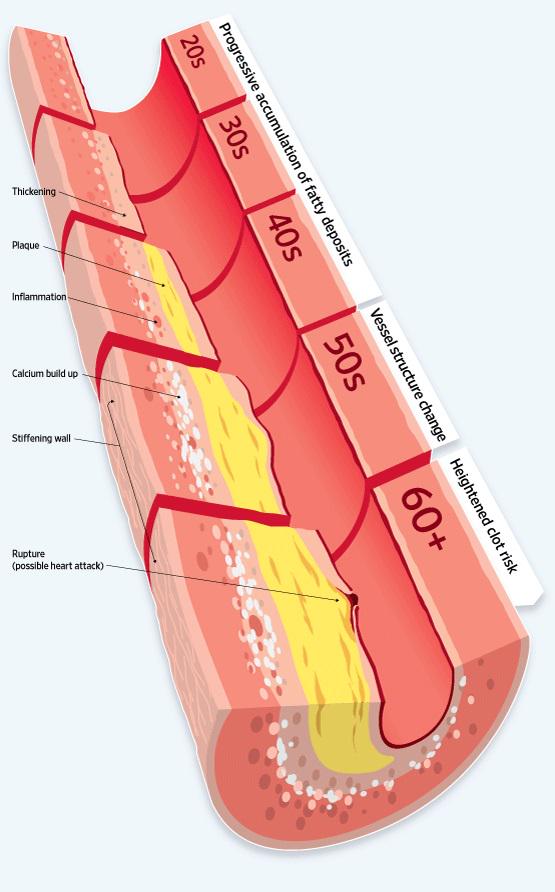

Calcified arteries, also known as arterial calcification, occur when calcium deposits build up in the walls of blood vessels. This process hardens and narrows the arteries, potentially leading to serious cardiovascular issues. But how exactly does this calcification develop?

Arterial calcification is a complex process involving several mechanisms:

- Calcium accumulation in the arterial walls

- Transformation of vascular smooth muscle cells into bone-like cells

- Imbalance in mineral metabolism

- Chronic inflammation

- Oxidative stress

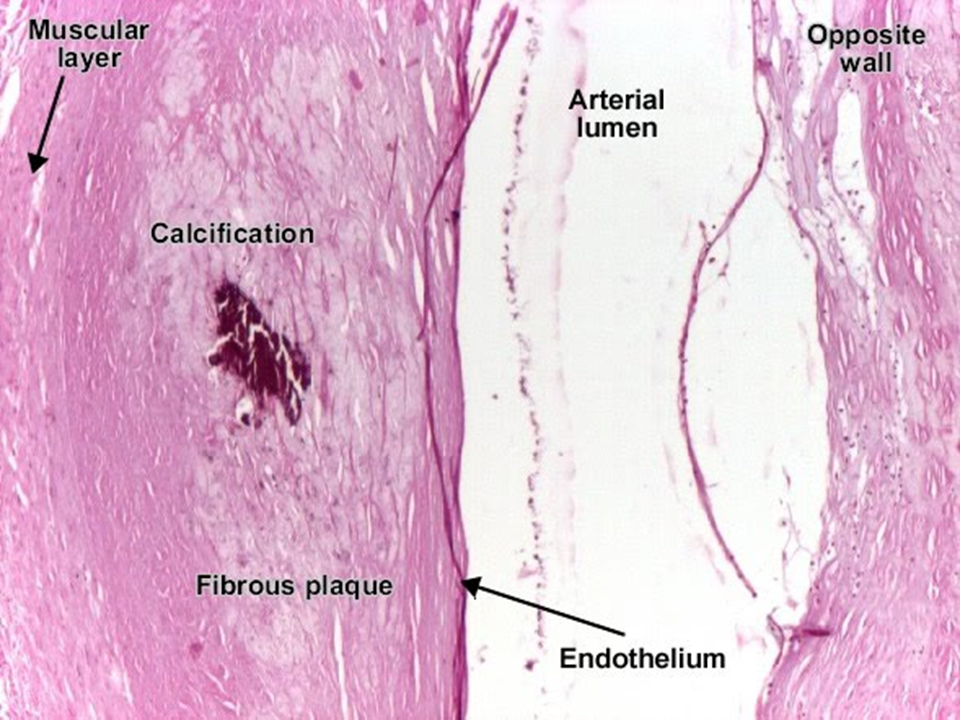

The calcification process often begins with damage to the inner lining of arteries, known as the endothelium. This damage can be caused by various factors, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, and diabetes. As the body attempts to repair this damage, calcium can accumulate in the arterial walls, leading to hardening and narrowing of the blood vessels.

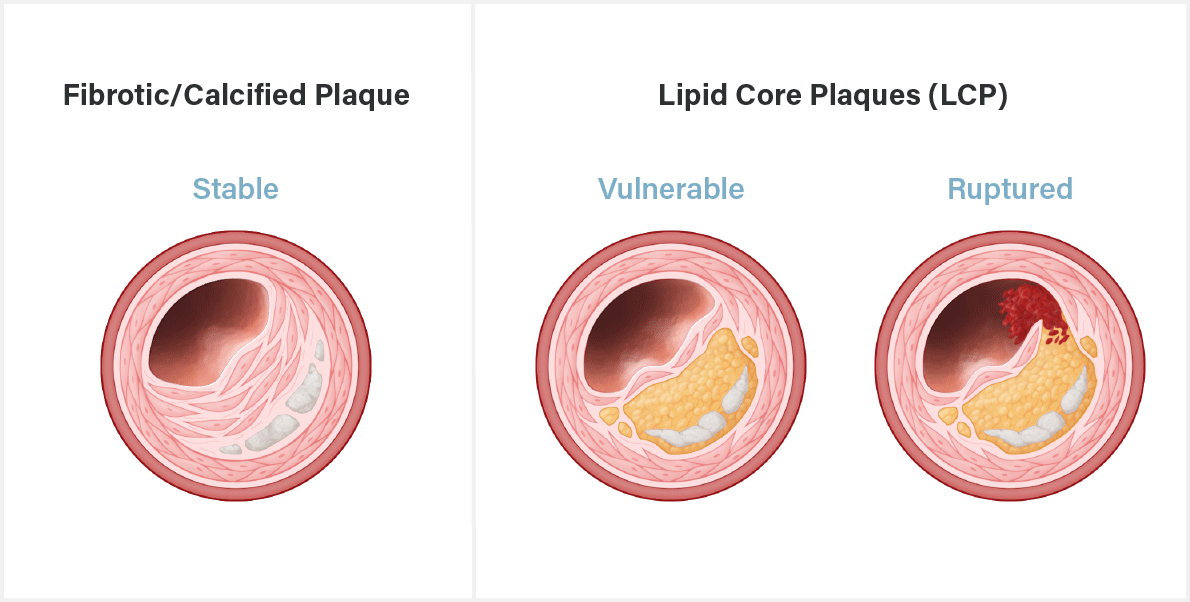

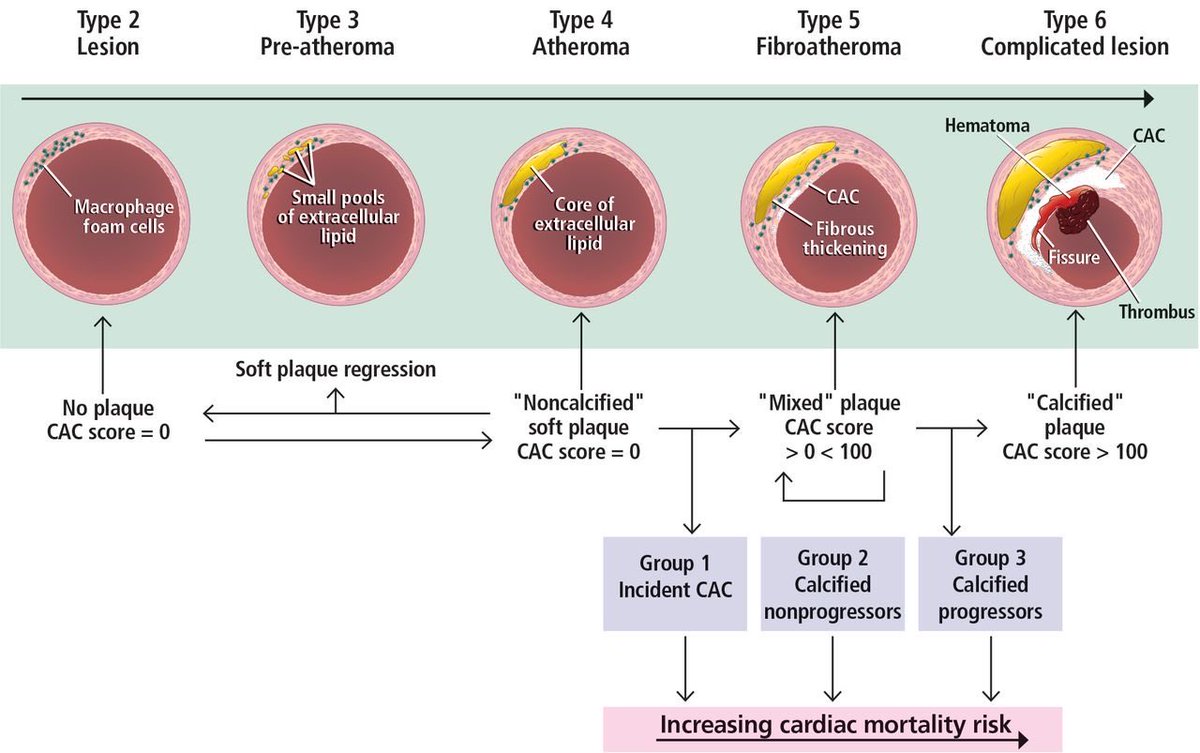

Types of Arterial Calcification

There are two main types of arterial calcification:

- Intimal calcification: Occurs within atherosclerotic plaques

- Medial calcification: Affects the middle layer of the artery wall

Both types can contribute to reduced arterial elasticity and increased cardiovascular risk.

Risk Factors for Artery Calcification: Who is Most Susceptible?

Certain factors can increase your risk of developing calcified arteries. Identifying these risk factors is crucial for prevention and early intervention. Who is most susceptible to arterial calcification?

- Advanced age

- Male gender

- Hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- High cholesterol levels

- Smoking

- Chronic kidney disease

- Obesity

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Family history of cardiovascular disease

Understanding these risk factors can help individuals take proactive steps to reduce their chances of developing calcified arteries. For instance, maintaining a healthy diet, regular exercise, and avoiding smoking can significantly lower your risk.

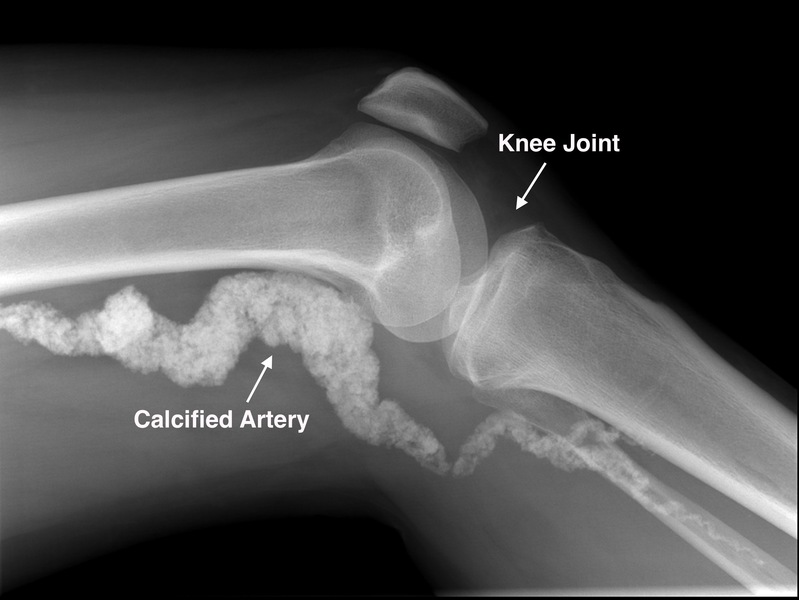

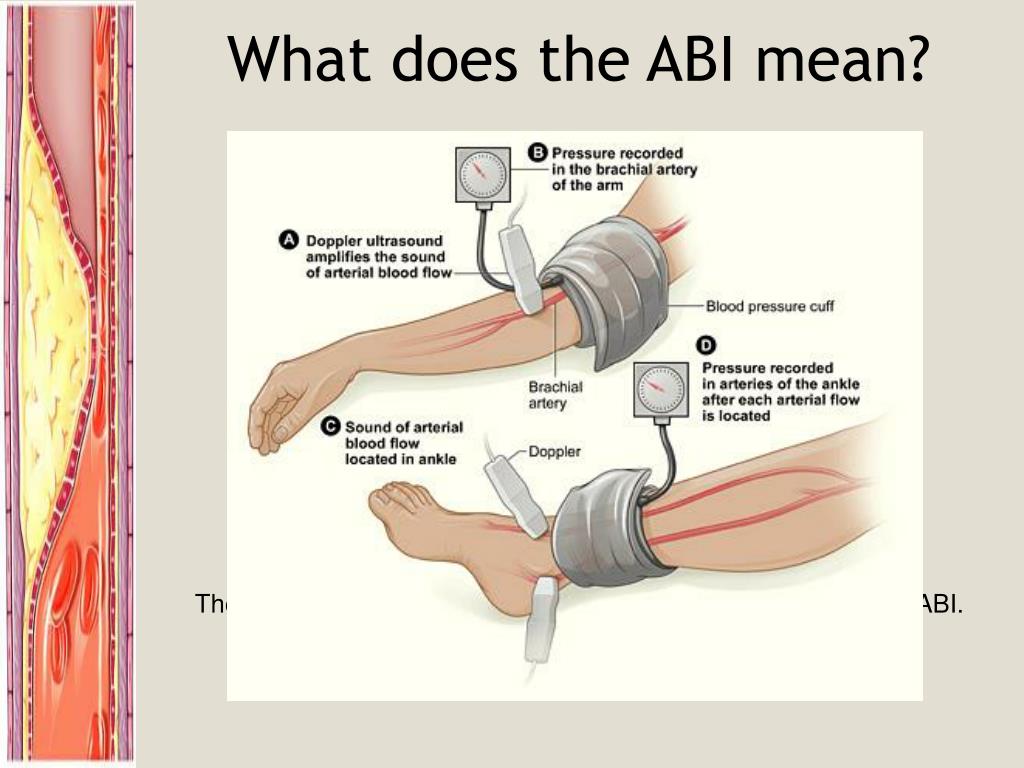

Diagnosing Coronary Artery Calcification: What Tests Are Used?

Early detection of arterial calcification is crucial for effective management and treatment. How is coronary artery calcification diagnosed? Several imaging techniques can be used to detect and quantify arterial calcification:

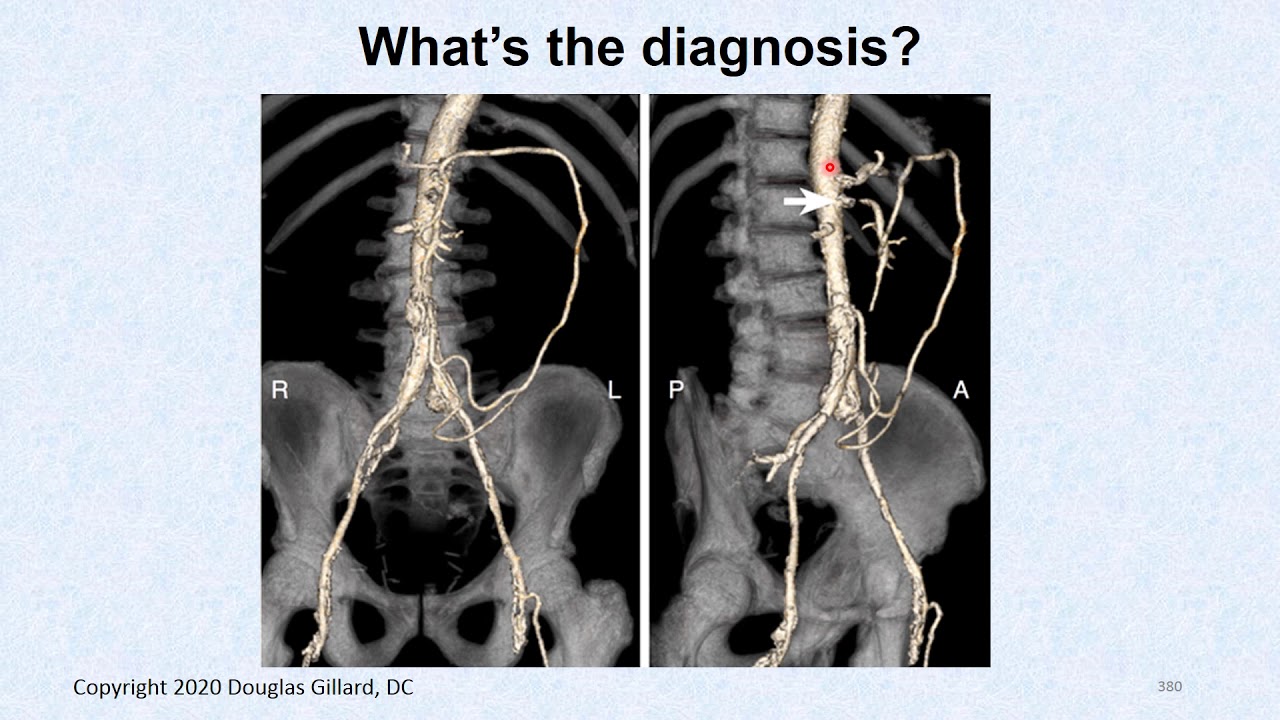

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: This is the most common and accurate method for detecting coronary artery calcification. It provides a calcium score that indicates the extent of calcification.

- Coronary Artery Calcium (CAC) Score: This score, derived from a CT scan, helps predict the risk of future cardiovascular events.

- Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS): This invasive procedure provides detailed images of the arterial walls and can detect early stages of calcification.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): Another invasive technique that offers high-resolution images of the arterial walls.

These diagnostic tools help healthcare providers assess the severity of arterial calcification and guide treatment decisions. Regular screenings may be recommended for individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease.

Treatment Options for Calcified Arteries: From Lifestyle Changes to Medical Interventions

Once diagnosed with calcified arteries, what treatment options are available? The approach to treating arterial calcification typically involves a combination of lifestyle modifications and medical interventions:

Lifestyle Changes

- Adopting a heart-healthy diet low in saturated fats and high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains

- Regular physical activity to improve cardiovascular health

- Quitting smoking and limiting alcohol consumption

- Stress management techniques such as meditation or yoga

Medical Interventions

- Medications to control blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels

- Statins to reduce cholesterol and potentially slow the progression of calcification

- Antiplatelet drugs to prevent blood clots

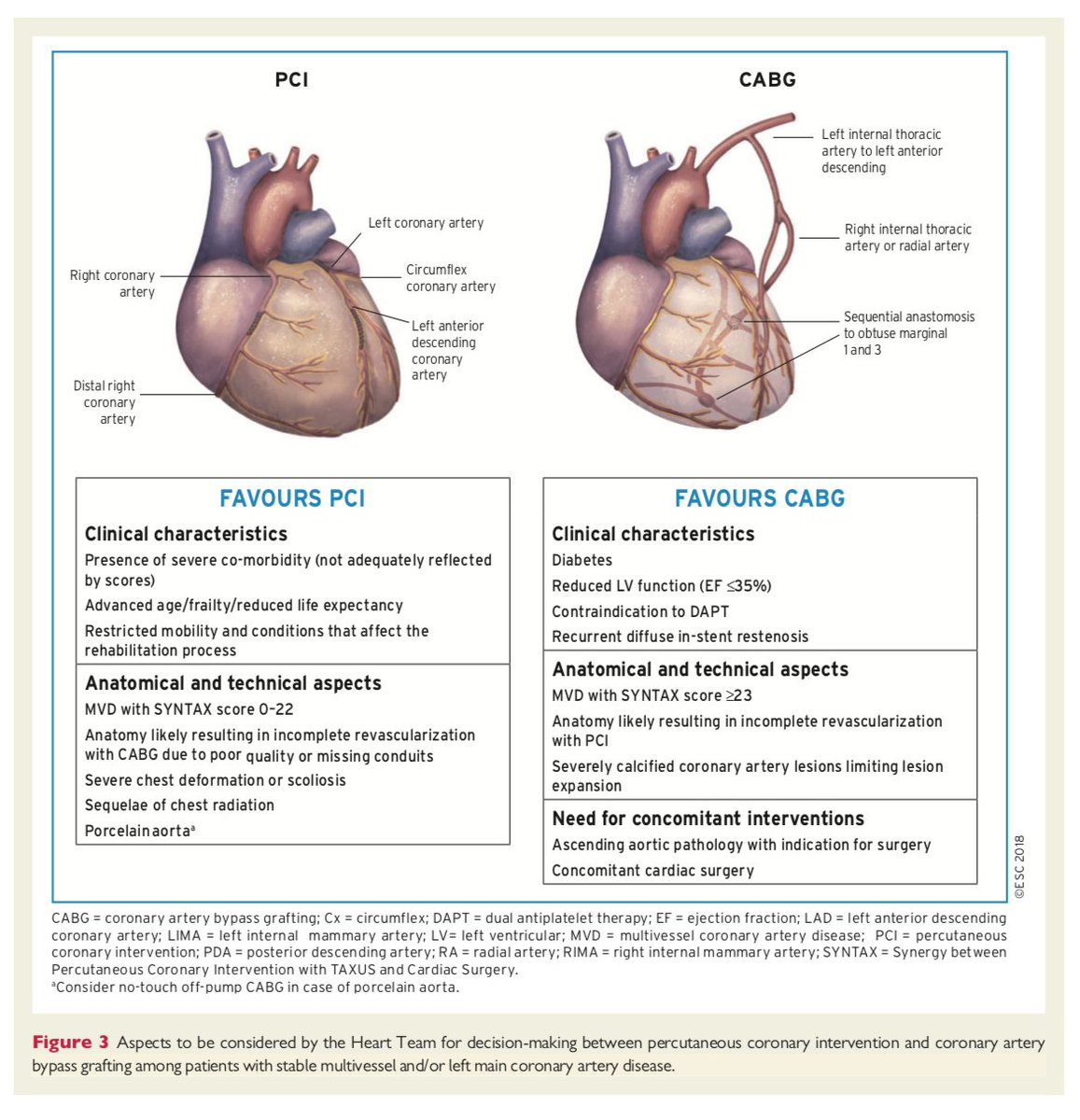

- In severe cases, procedures such as angioplasty or bypass surgery may be necessary

It’s important to note that treatment plans are often tailored to individual patients based on the severity of their condition and overall health status.

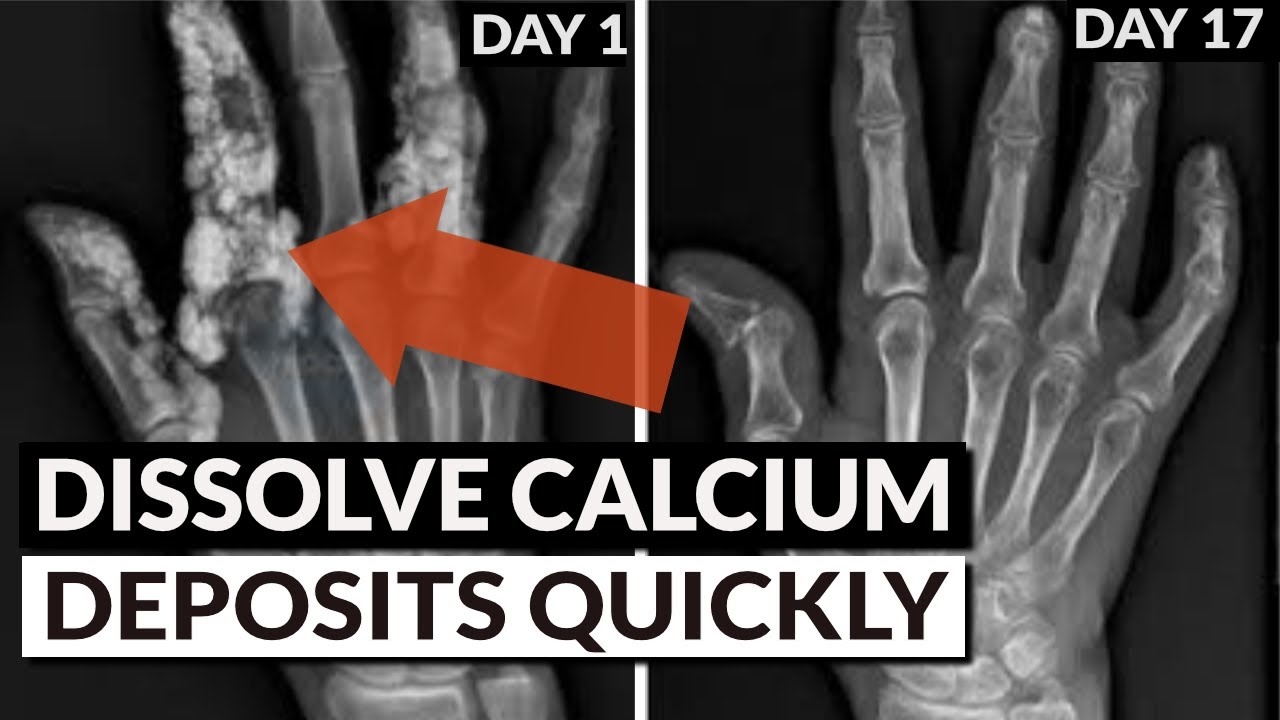

Can Arterial Calcification Be Reversed? Exploring Current Research and Possibilities

A common question among those diagnosed with calcified arteries is whether the condition can be reversed. While complete reversal of arterial calcification is challenging, current research suggests that slowing or potentially halting its progression may be possible.

Several studies have explored potential strategies for addressing arterial calcification:

- Vitamin K supplementation: Some research indicates that vitamin K may help prevent calcium from depositing in arterial walls.

- Magnesium intake: Adequate magnesium levels may help regulate calcium metabolism and potentially reduce calcification.

- Chelation therapy: This controversial treatment involves using chemicals to remove calcium deposits, but its effectiveness and safety are still under investigation.

- Emerging pharmaceutical approaches: Researchers are exploring drugs that target specific pathways involved in the calcification process.

While these approaches show promise, more research is needed to fully understand their effectiveness and safety. Currently, the focus remains on preventing further progression of calcification through lifestyle changes and medical management.

Preventing Artery Calcification: Proactive Steps for Cardiovascular Health

Prevention is key when it comes to arterial calcification. What proactive steps can individuals take to maintain cardiovascular health and reduce their risk of developing calcified arteries?

- Maintain a healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins

- Engage in regular physical activity, aiming for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week

- Manage stress through relaxation techniques or mindfulness practices

- Control blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels through lifestyle changes and medication if necessary

- Quit smoking and limit alcohol consumption

- Maintain a healthy weight

- Stay hydrated and limit excessive salt intake

- Consider supplements like vitamin D and K2, under the guidance of a healthcare provider

By adopting these healthy habits, individuals can significantly reduce their risk of developing calcified arteries and improve their overall cardiovascular health.

The Role of Genetics in Arterial Calcification: Understanding Your Inherited Risk

While lifestyle factors play a significant role in the development of calcified arteries, genetics also contribute to an individual’s susceptibility. How do genetic factors influence arterial calcification?

Research has identified several genetic variations that may increase the risk of arterial calcification:

- Genes involved in calcium and phosphate metabolism

- Genetic factors affecting vascular smooth muscle cell function

- Variations in genes related to lipid metabolism and inflammation

Understanding your genetic predisposition can help guide preventive strategies and early interventions. However, it’s important to remember that having a genetic risk doesn’t guarantee you’ll develop calcified arteries. Lifestyle choices still play a crucial role in managing this risk.

Genetic Testing for Arterial Calcification Risk

Genetic testing can provide insights into an individual’s risk of developing calcified arteries. This information can be valuable for:

- Identifying high-risk individuals who may benefit from early screening

- Guiding personalized prevention strategies

- Informing treatment decisions in diagnosed cases

However, genetic testing should always be conducted under the guidance of a healthcare professional who can interpret the results and provide appropriate counseling.

Emerging Therapies and Future Directions in Treating Calcified Arteries

As our understanding of arterial calcification grows, researchers are exploring new and innovative approaches to treatment. What emerging therapies show promise in addressing calcified arteries?

MicroRNA-based Therapies

MicroRNAs play a crucial role in regulating gene expression and have been implicated in the development of arterial calcification. Researchers are investigating the potential of microRNA-based therapies to:

- Inhibit the progression of calcification

- Promote the regression of existing calcium deposits

- Modulate the behavior of vascular smooth muscle cells

Nanotechnology Approaches

Nanotechnology offers exciting possibilities for targeted drug delivery and imaging of calcified arteries. Potential applications include:

- Nanoparticles designed to dissolve calcium deposits

- Nano-scale imaging agents for improved detection of early-stage calcification

- Targeted delivery of drugs to affected areas of the arteries

Stem Cell Therapies

Stem cell research is exploring the potential of using these versatile cells to:

- Regenerate damaged arterial tissue

- Modulate the inflammatory response associated with calcification

- Promote the differentiation of healthy vascular cells

While these emerging therapies show promise, they are still in various stages of research and development. Clinical trials will be necessary to establish their safety and efficacy before they become widely available treatment options.

Living with Calcified Arteries: Strategies for Managing Your Condition

For individuals diagnosed with calcified arteries, managing the condition effectively is crucial for maintaining quality of life and reducing the risk of complications. What strategies can help in living with calcified arteries?

Regular Monitoring and Follow-up

Consistent medical supervision is essential for managing calcified arteries. This typically involves:

- Regular check-ups with your healthcare provider

- Periodic imaging tests to monitor the progression of calcification

- Blood tests to assess cardiovascular risk factors

Adherence to Treatment Plans

Following your prescribed treatment plan is crucial. This may include:

- Taking medications as directed

- Attending scheduled medical appointments

- Participating in recommended cardiac rehabilitation programs

Lifestyle Modifications

Adopting and maintaining heart-healthy habits is key to managing calcified arteries:

- Following a balanced, nutrient-rich diet

- Engaging in regular physical activity as advised by your healthcare provider

- Managing stress through relaxation techniques or counseling

- Avoiding tobacco use and limiting alcohol consumption

Emotional and Psychological Support

Living with a chronic condition can be challenging. Consider:

- Joining support groups for individuals with cardiovascular conditions

- Seeking counseling or therapy to address anxiety or depression related to your diagnosis

- Practicing mindfulness or meditation to improve overall well-being

By implementing these strategies and working closely with your healthcare team, you can effectively manage calcified arteries and maintain a good quality of life.

The Impact of Diet on Arterial Calcification: Foods to Embrace and Avoid

Diet plays a crucial role in managing and preventing arterial calcification. What foods should you embrace, and which ones should you avoid to support arterial health?

Foods to Embrace

Incorporating these nutrient-rich foods into your diet can help support cardiovascular health:

- Leafy green vegetables (spinach, kale, collard greens)

- Fatty fish rich in omega-3 fatty acids (salmon, mackerel, sardines)

- Nuts and seeds (almonds, walnuts, flaxseeds)

- Whole grains (oats, quinoa, brown rice)

- Berries (strawberries, blueberries, raspberries)

- Legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas)

- Olive oil and avocados for healthy fats

Foods to Avoid or Limit

Reducing or eliminating these foods can help manage arterial calcification:

- Processed foods high in trans fats and saturated fats

- Sugary beverages and excessive added sugars

- Red and processed meats

- High-sodium foods

- Refined carbohydrates (white bread, pastries, sugary cereals)

Remember, a balanced diet is key. While calcium is essential for overall health, excessive calcium supplementation may contribute to arterial calcification in some individuals. Always consult with a healthcare provider or registered dietitian for personalized dietary advice.

The Mediterranean Diet and Arterial Health

The Mediterranean diet has shown promise in promoting cardiovascular health and potentially reducing the risk of arterial calcification. This dietary pattern emphasizes:

- Plant-based foods

- Healthy fats from olive oil and nuts

- Moderate consumption of fish and poultry

- Limited red meat intake

- Moderate red wine consumption (if desired and approved by a healthcare provider)

Adopting a Mediterranean-style diet, along with other healthy lifestyle habits, may help support arterial health and overall well-being.

Current understanding of coronary artery calcification

1. Kalra SS, Shanahan CM. Vascular calcification and hypertension: cause and effect. Ann Med. 2012;44(Suppl 1):S85–S92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Greenland P, LaBree L, Azen SP, et al. Coronary artery calcium score combined with Framingham score for risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals. JAMA. 2004;291:210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Demer LL, Tintut Y. Vascular calcification: pathobiology of a multifaceted disease. Circulation. 2008;117:2938–2948. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Wong ND, Kouwabunpat D, Vo AN, et al. Coronary calcium and atherosclerosis by ultrafast computed tomography in asymptomatic men and women: relation to age and risk factors. Am Heart J. 1994;127:422–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Goel M, Wong ND, Eisenberg H, et al. Risk factor correlates of coronary calcium as evaluated by ultrafast computed tomography. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:977–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Kronmal RA, McClelland RL, Detrano R, et al. Risk factors for the progression of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic subjects: results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Circulation. 2007;115:2722–2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kronmal RA, McClelland RL, Detrano R, et al. Risk factors for the progression of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic subjects: results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Circulation. 2007;115:2722–2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Spence LA, Weaver CM. Calcium intake, vascular calcification, and vascular disease. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Raffield LM, Agarwal S, Cox AJ, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of calcium intake for associations with vascular calcification and mortality in individuals with type 2 diabetes from the diabetes heart study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1029–1035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Demer LL, Tintut Y. Vascular calcification: pathobiology of a multifaceted disease. Circulation. 2008;117:2938–2948. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Johnson RC, Leopold JA, Loscalzo J. Vascular calcification: pathobiological mechanisms and clinical implications. Circ Res. 2006;99:1044–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2006;99:1044–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Abedin M, Tintut Y, Demer LL. Vascular calcification: mechanisms and clinical ramifications. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1161–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Goodman WG, London G, Amann K, et al. Vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:572–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Wang L, Jerosch-Herold M, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. Coronary artery calcification and myocardial perfusion in asymptomatic adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1018–1026. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Spence LA, Weaver CM. Calcium intake, vascular calcification, and vascular disease. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Ix JH, Katz R, de Boer IH, et al. Fetuin-A is inversely associated with coronary artery calcification in community-living persons: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Clin Chem. 2012;58:887–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Leopold J. MicroRNAs regulate vascular medial calcification. Cells. 2014;3:963–980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MicroRNAs regulate vascular medial calcification. Cells. 2014;3:963–980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Goettsch C, Rauner M, Pacyna N, et al. MiR-125b regulates calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1594–1600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Liao XB, Zhang ZY, Yuan K, et al. MiR-133a modulates osteogenic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3344–3352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Cui RR, Li SJ, Liu LJ, et al. MicroRNA-204 regulates vascular smooth muscle cell calcification in vitro and in vivo. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;96:320–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Dhore CR, Cleutjens JP, Lutgens E, et al. Differential expression of bone matrix regulatory proteins in human atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1998–2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Bostrom KI, Rajamannan NM, Towler DA. The regulation of valvular and vascular sclerosis by osteogenic morphogens. Circ Res. 2011;109:564–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Circ Res. 2011;109:564–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Lim K, Lu TS, Molostvov G, et al. Vascular Klotho deficiency potentiates the development of human artery calcification and mediates resistance to fibroblast growth factor 23. Circulation. 2012;125:2243–2255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Taïbi F, Metzinger-Le Meuth V, Massy ZA, et al. MiR-223: An inflammatory oncomiR enters the cardiovascular field. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1001–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Taïbi F, Metzinger-Le Meuth V, Massy ZA, et al. MiRNA-221 and miRNA-222 synergistically function to promote vascular calcification. Cell Biochem Funct. 2014;32:209–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Budoff MJ, Hokanson JE, Nasir K, et al. Progression of coronary artery calcium predicts all-cause mortality. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2010;3:1229–1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Hou Z, Lu B, Gao Y, et al. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography and calcium score for major adverse cardiac events in outpatients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:990–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:990–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Saremi A, Bahn G, Reaven PD. Progression of vascular calcification is increased with statin use in the veterans affairs diabetes trial (VADT) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2390–2392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Coylewright M, Rice K, Budoff MJ, et al. Differentiation of severe coronary artery calcification in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:616–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Coylewright M, Rice K, Budoff MJ, et al. Differentiation of severe coronary artery calcification in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:616–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Ehara S, Kobayashi Y, Yoshiyama M, et al. Spotty calcification typifies the culprit plaque in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2004;110:3424–3429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. van Velzen JE, de Graaf FR, Jukema JW, et al. Comparison of the relation between the calcium score and plaque characteristics in patients with acute coronary syndrome versus patients with stable coronary artery disease, assessed by computed tomography angiography and virtual histology intravascular ultrasound. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:658–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Comparison of the relation between the calcium score and plaque characteristics in patients with acute coronary syndrome versus patients with stable coronary artery disease, assessed by computed tomography angiography and virtual histology intravascular ultrasound. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:658–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Ix JH, et al. Calcium density of coronary artery plaque and risk of incident cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2014;311:271–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. de Araújo Gonçalves P, Garcia-Garcia HM, Carvalho MS, et al. Diabetes as an independent predictor of high atherosclerotic burden assessed by coronary computed tomography angiography: the coronary artery disease equivalent revisited. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29:1105–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Anand DV, Lim E, Hopkins D, et al. Risk stratification in uncomplicated type 2 diabetes: prospective evaluation of the combined use of coronary artery calcium imaging and selective myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:713–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Becker A, Leber AW, Becker C, et al. Predictive value of coronary calcifications for future cardiac events in asymptomatic patients with diabetes mellitus: a prospective study in 716 patients over 8 years. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2008;8:27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Elkeles RS, Godsland IF, Feher MD, et al. Coronary calcium measurement improves prediction of cardiovascular events in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes: the PREDICT study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2244–2251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Scholte AJ, Schuijf JD, Kharagjitsingh AV, et al. Prevalence of coronary artery disease and plaque morphology assessed by multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography and calcium scoring in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes. Heart. 2008;94:290–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heart. 2008;94:290–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Budoff MJ, Nasir K, McClelland RL, et al. Coronary calcium predicts events better with absolute calcium scores than age-sex-race/ethnicity percentiles. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:345–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Greenland P, LaBree L, Azen SP, et al. Coronary artery calcium score combined with Framingham score for risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals. JAMA. 2004;291:210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Yamamoto H, Imazu M, Hattori Y, et al. Predicting angiographic narrowing > or = 50% in diameter in each of the three major arteries by amounts of calcium detected by electron beam computed tomographic scanning in patients with chest pain. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:778–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Budoff MJ, Malpeso JM. Is coronary artery calcium the key to assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults? J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Hou ZH, Lu B, Gao Y, et al. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography and calcium score for major adverse cardiac events in outpatients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:990–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hou ZH, Lu B, Gao Y, et al. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography and calcium score for major adverse cardiac events in outpatients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:990–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Hulten E, Bittencourt MS, Ghoshhajra B, et al. Incremental prognostic value of coronary artery calcium score versus CT angiography among symptomatic patients without known coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233:190–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Choi EK, Choi SI, Rivera JJ, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography as a screening tool for the detection of occult coronary artery disease in asymptomatic individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:357–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Choi EK, Choi SI, Rivera JJ, et al. Treatment of asymptomatic adults with elevated coronary calcium scores with atorvastatin, vitamin C, and vitamin E: the St. Francis Heart Study randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Motro M, Shemesh J. Calcium channel blocker nifedipine slows down progression of coronary calcification in hypertensive patients compared with diuretics. Hypertension. 2001;37:1410–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Motro M, Shemesh J. Calcium channel blocker nifedipine slows down progression of coronary calcification in hypertensive patients compared with diuretics. Hypertension. 2001;37:1410–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Manson JE, Allison MA, Rossouw JE, et al. Estrogen therapy and coronary-artery calcification. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2591–2602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Chertow GM, Burke SK, Raggi P. Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:245–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Qunibi W, Moustafa M, Muenz LR, et al. A 1-year randomized trial of calcium acetate versus sevelamer on progression of coronary artery calcification in hemodialysis patients with comparable lipid control: the Calcium Acetate Renagel Evaluation-2 (CARE-2) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:952–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Budoff MJ, Ahmadi N, Gul KM, et al. Aged garlic extract supplemented with B vitamins, folic acid and L-arginine retards the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2009;49:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prev Med. 2009;49:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Zeb I, Ahmadi N, Nasir K, et al. Aged garlic extract and coenzyme Q10 have favorable effect on inflammatory markers and coronary atherosclerosis progression: A randomized clinical trial. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2012;3:185–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Zhang YJ, Zhu LL, Bourantas CV, et al. The impact of everolimus versus other rapamycin derivative-eluting stents on clinical outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis of 16 randomized trials. J Cardiol. 2014;64:185–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Bourantas CV, Zhang YJ, Garg S, et al. Prognostic implications of coronary calcification in patients with obstructive coronary artery disease treated by percutaneous coronary intervention: a patient-level pooled analysis of 7 contemporary stent trials. Heart. 2014;100:1158–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Fitzgerald PJ, Ports TA, Yock PG. Contribution of localized calcium deposits to dissection after angioplasty. An observational study using intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 1992;86:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

An observational study using intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 1992;86:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Díaz JF, Gómez-Menchero A, Cardenal R, et al. Extremely high-pressure dilation with a new noncompliant balloon. Tex Heart Inst J. 2012;39:635–638. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Barath P, Fishbein MC, Vari S, et al. Cutting balloon: a novel approach to percutaneous angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:1249–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Mauri L, Bonan R, Weiner BH, et al. Cutting balloon angioplasty for the prevention of restenosis: results of the cutting balloon global randomized trial. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1079–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Albiero R, Silber S, Di Mario C, et al. Cutting balloon versus conventional balloon angioplasty for the treatment of in-stent restenosis: results of the restenosis cutting balloon evaluation trial (RESCUT) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:943–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:e574–e651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:e574–e651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Moussa I, Ellis SG, Jones MI, et al. Impact of coronary culprit lesion calcium in patients undergoing paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation (a TAXUS-IV sub study) Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1242–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Bangalore S, Vlachos HA, Selzer F, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention of moderate to severe calcified coronary lesions: insights from the national heart, lung, and blood institute dynamic registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77:22–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Zhang BC, Wang C, Li WH, et al. Clinical outcome of drug-eluting versus bare metal stents in patients with calcified coronary lesions: a meta-analysis. Intern Med J. 2015;45:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Intern Med J. 2015;45:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Zimarino M, Corcos T, Bramucci E, et al. Rotational atherectomy: a “survivor” in the drug-eluting stent era. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2012;13:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. MacIsaac AI, Bass TA, Buchbinder M, et al. High speed rotational atherectomy: outcome in calcified and noncalcified coronary artery lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:731–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Kume T, Okura H, Kawamoto T, et al. Assessment of the histological characteristics of coronary arterial plaque with severe calcification. Circ J. 2007;71:643–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Cockburn J, Hildick-Smith D, Cotton J, et al. Contemporary clinical outcomes of patients treated with or without rotational coronary atherectomy–an analysis of the UK central cardiac audit database. Int J Cardiol. 2014;170:381–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Tomey MI, Kini AS, Sharma SK. Current status of rotational atherectomy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Lee Y, Tanaka A, Mori N, et al. Thin-strut drug-eluting stents are more favorable for severe calcified lesions after rotational atherectomy than thick-strut drug-eluting stents. J Invasive Cardiol. 2014;26:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Bittl JA, Sanborn TA, Tcheng JE, et al. Clinical success, complications and restenosis rates with excimer laser coronary angioplasty. The percutaneous excimer laser coronary angioplasty registry. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:1533–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Mintz GS, Kovach JA, Pichard AD, et al. Intravascular ultrasound findings after excimer laser coronary angioplasty. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1996;37:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Badr S, Ben-Dor I, Dvir D, et al. The state of the excimerlaser for coronary intervention in the drug-eluting stent era. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2013;14:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Parikh K, Chandra P, Choksi N, et al. Safety and feasibility of orbital atherectomy for the treatment of calcified coronary lesions: the ORBIT I trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:1134–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Safety and feasibility of orbital atherectomy for the treatment of calcified coronary lesions: the ORBIT I trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:1134–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Chambers JW, Feldman RL, Himmelstein SI, et al. Pivotal trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the orbital atherectomy system in treating de novo, severely calcified coronary lesions (ORBIT II) JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:510–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Castagna MT, Mintz GS, Ohlmann P, et al. Incidence, location, magnitude, and clinical correlates of saphenous vein graft calcification: an intravascular ultrasound and angiographic study. Circulation. 2005;111:1148–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coronary Artery Calcification: Causes, Treatment, and Outlook

Calcium is a mineral your body needs for vital functions and good health. Calcium helps keep your bones and teeth strong, but it’s also involved in heart function. Sometimes, calcium deposits can also have a negative effect on your health.

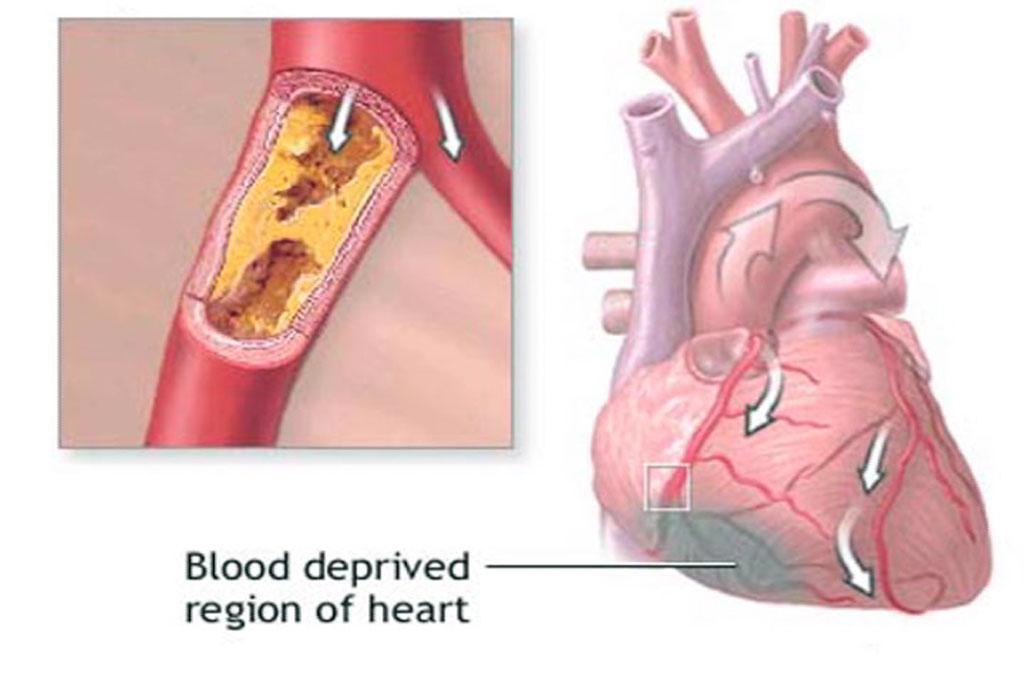

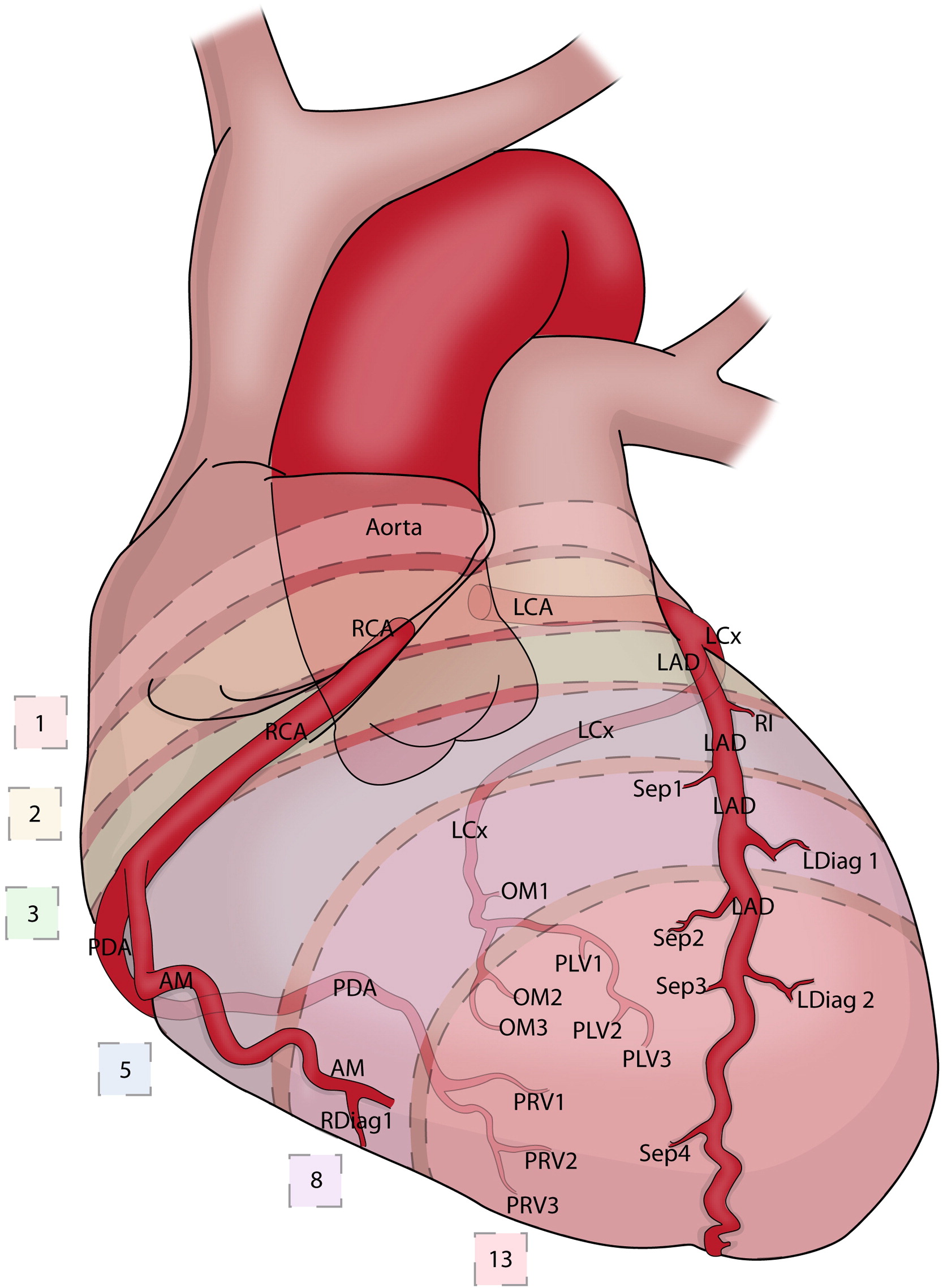

Coronary artery calcifications occur when calcium builds up in the arteries that supply blood to the heart. This buildup can lead to coronary artery disease and increases your risk of a heart attack.

Keep reading to find out why and how coronary artery calcification occurs, as well as tips for prevention and treatment.

Key terms

This article uses the following terms. They’re similar but have different meanings, so it’s important to know what each means.

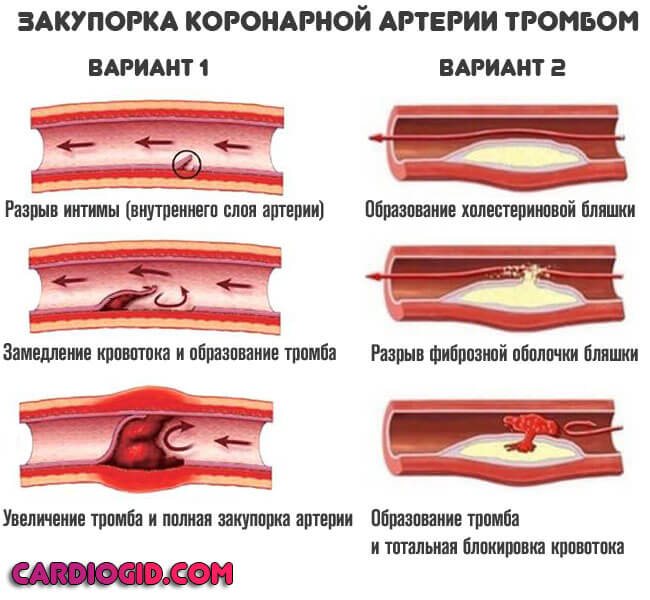

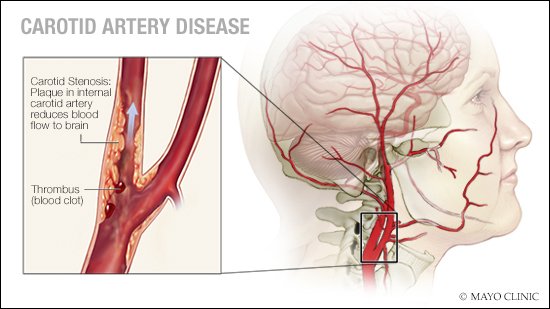

- Atherosclerosis is when fatty deposits called plaque build up in your arteries. Atherosclerosis can cause your artery to narrow. The plaques can break off and cause a blood clot.

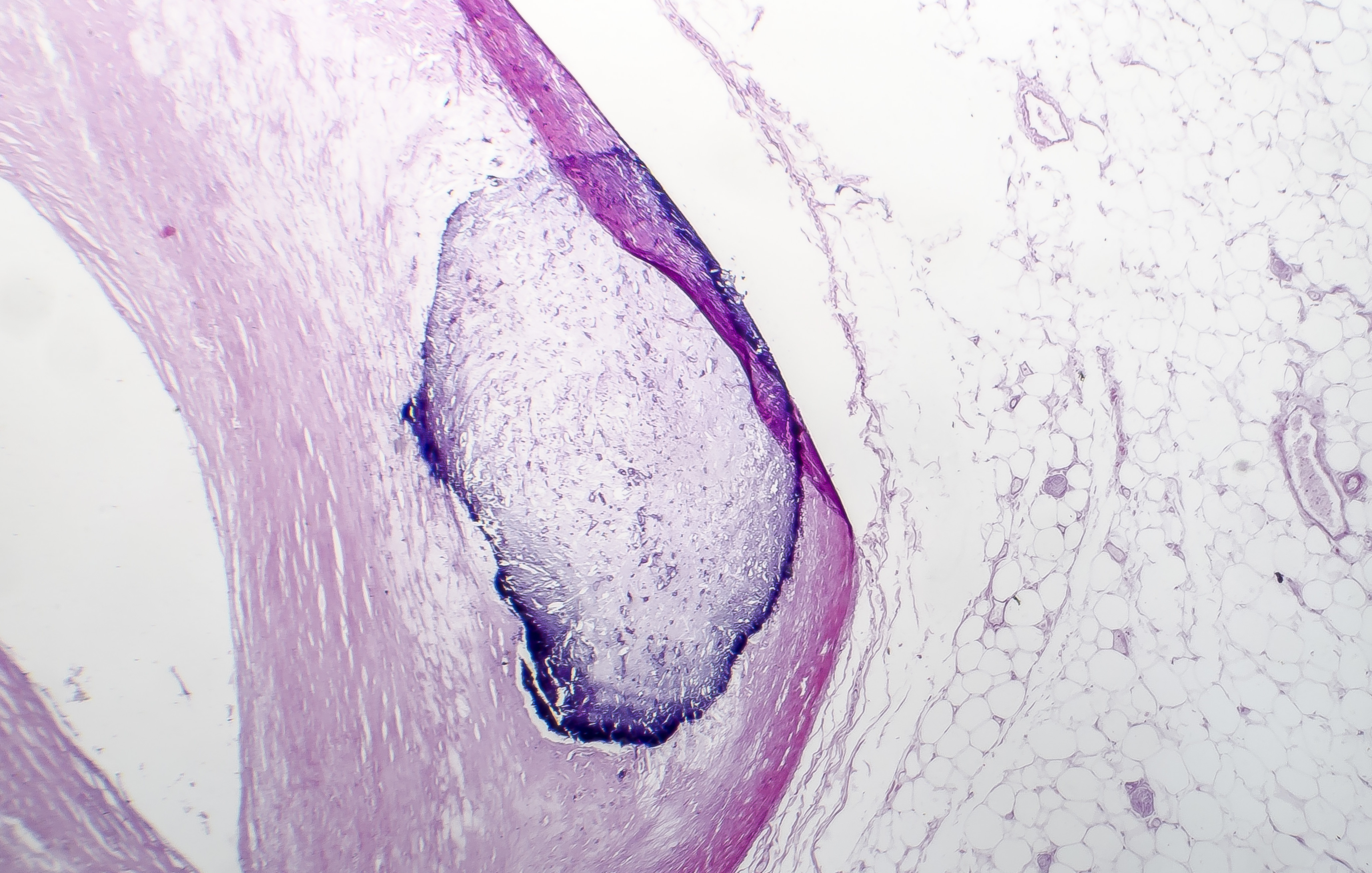

- Coronary artery calcification is the buildup of calcium in the arteries that supply blood to your heart. Calcification often occurs at the same time as atherosclerosis.

- Coronary artery disease, also known as CAD, occurs when the heart doesn’t get enough oxygen and blood.

This is usually due to atherosclerosis.

This is usually due to atherosclerosis.

Was this helpful?

Calcium is naturally present in your body — mostly in your bones and teeth. However, about 1 percent of your body’s calcium is circulating in your blood.

Researchers believe that coronary artery calcifications may occur due to the release of calcium when smooth muscle cells die in the heart’s arteries.

Also, macrophages (immune system cells) in the arteries may release inflammatory compounds that allow calcium to deposit more easily. Over time, the calcium deposits combine to form “speckles” or spots that can later develop into sheets or fragments.

Coronary artery calcification is a concern because it’s a precursor for atherosclerosis. This is a buildup of plaque in the arteries that causes blood to flow less effectively. The plaque can also break off and cause a heart attack or stroke.

Some medical conditions can cause genetic changes that result in coronary artery calcifications. These conditions can often cause a person to develop coronary artery calcifications at a much earlier age. Examples include:

Examples include:

- Gaucher’s disease type 3C

- Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome

- idiopathic basal ganglia calcification

- pseudoxanthoma elasticum

- Singleton-Merten syndrome

Coronary artery calcification is most common in older adults, with calcium buildup starting around age 40. Researchers estimate that by age 70, 90 percent of men and 67 percent of women have coronary artery calcification.

Men experience coronary artery calcifications at a younger age than women, about 10 to 15 years earlier. Researchers think this is due to estrogen being protective against calcium deposits.

In addition to rare medical conditions that cause calcifications in young people, some chronic medical conditions can increase your risk. Examples include:

- metabolic syndrome

- hypertension (high blood pressure)

- diabetes

- dyslipidemia (irregular cholesterol levels)

- obesity

- chronic kidney disease

Tobacco use is also a risk factor for coronary artery calcification.

The presence of coronary artery calcifications doesn’t usually cause symptoms. But these calcifications tend to occur alongside other heart conditions that do have symptoms.

Symptoms of atherosclerosis and CAD include:

- chest pain

- chest tightness

- shortness of breath

If you’re experiencing these symptoms, your calcifications may have advanced to the point of atherosclerosis or CAD. If this is the case for you, talk with a doctor as soon as possible.

If your calcifications advance to CAD, it could lead to a heart attack. Heart attack symptoms also include weakness, nausea, shortness of breath, and pain in the arms or shoulder.

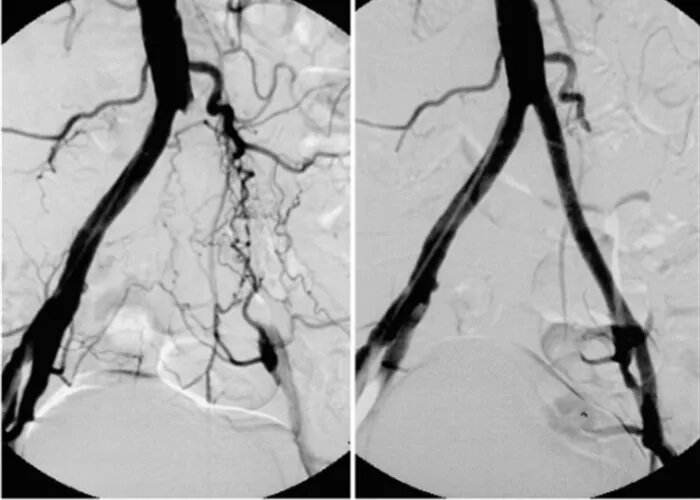

Doctors can diagnose coronary artery calcification using imaging studies. Unfortunately, they may only be able to see the calcification when there is significant calcium buildup in the coronary arteries.

If you have high cholesterol and your doctor suspects coronary artery calcifications, they’ll likely order a computed tomography or CT scan. A CT scan is a painless imaging test that allows doctors to “score” the amount of calcium present.

A CT scan is a painless imaging test that allows doctors to “score” the amount of calcium present.

More invasive tests for coronary artery calcifications exist. These tests usually involve threading a small, thin catheter through your thigh or forearm to your coronary arteries. Examples include cardiac intravascular ultrasound and intravascular optical coherence tomography.

Know your coronary artery calcium score

If you undergo a coronary artery calcium CT scan, your doctor will assign you a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score, often called an Agatston score. This measures the scale of your calcium buildup. The higher your CAC score is, the more severe your calcium buildup is. Levels of the score are:

- 0: no identifiable disease

- 1 to 99: mild disease

- 100 to 399: moderate disease

- More than 400: severe disease

Was this helpful?

Treatments for coronary artery calcification depend on how severe the calcifications are. If the calcifications don’t show signs of severe disease, a doctor will usually recommend risk factor modification. This means you change aspects of your lifestyle to reduce the chance more calcium will build up.

If the calcifications don’t show signs of severe disease, a doctor will usually recommend risk factor modification. This means you change aspects of your lifestyle to reduce the chance more calcium will build up.

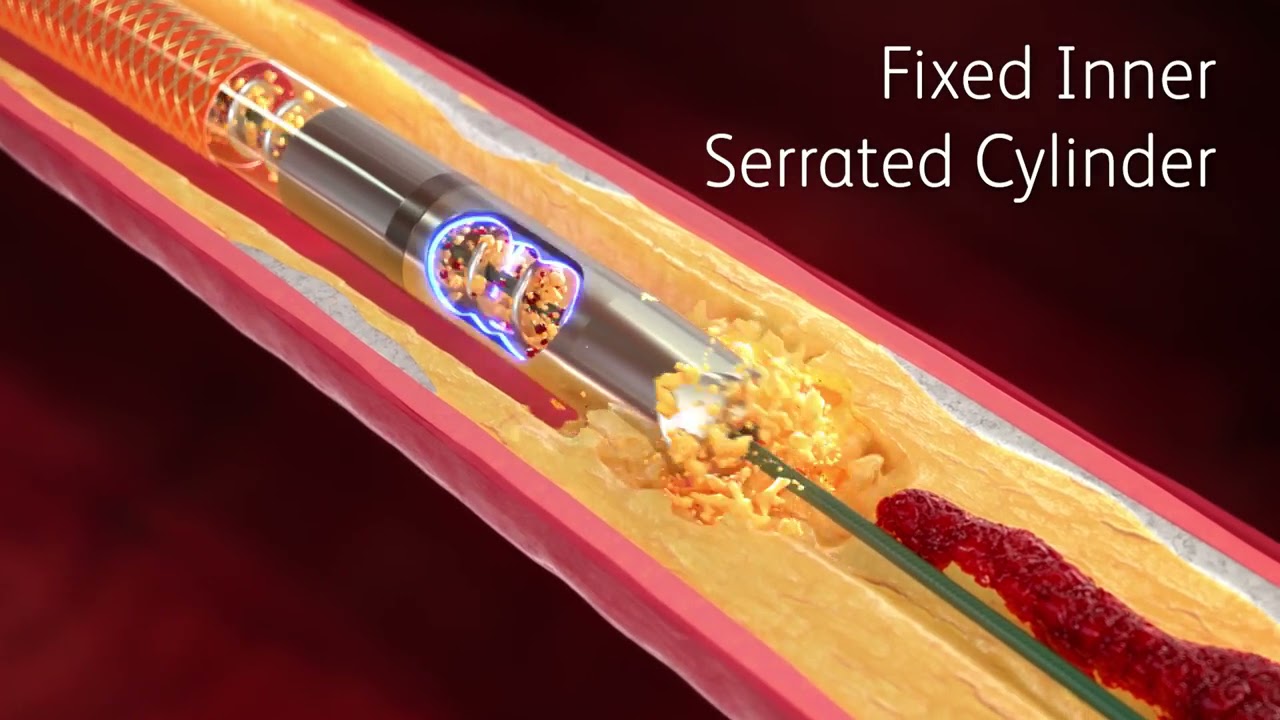

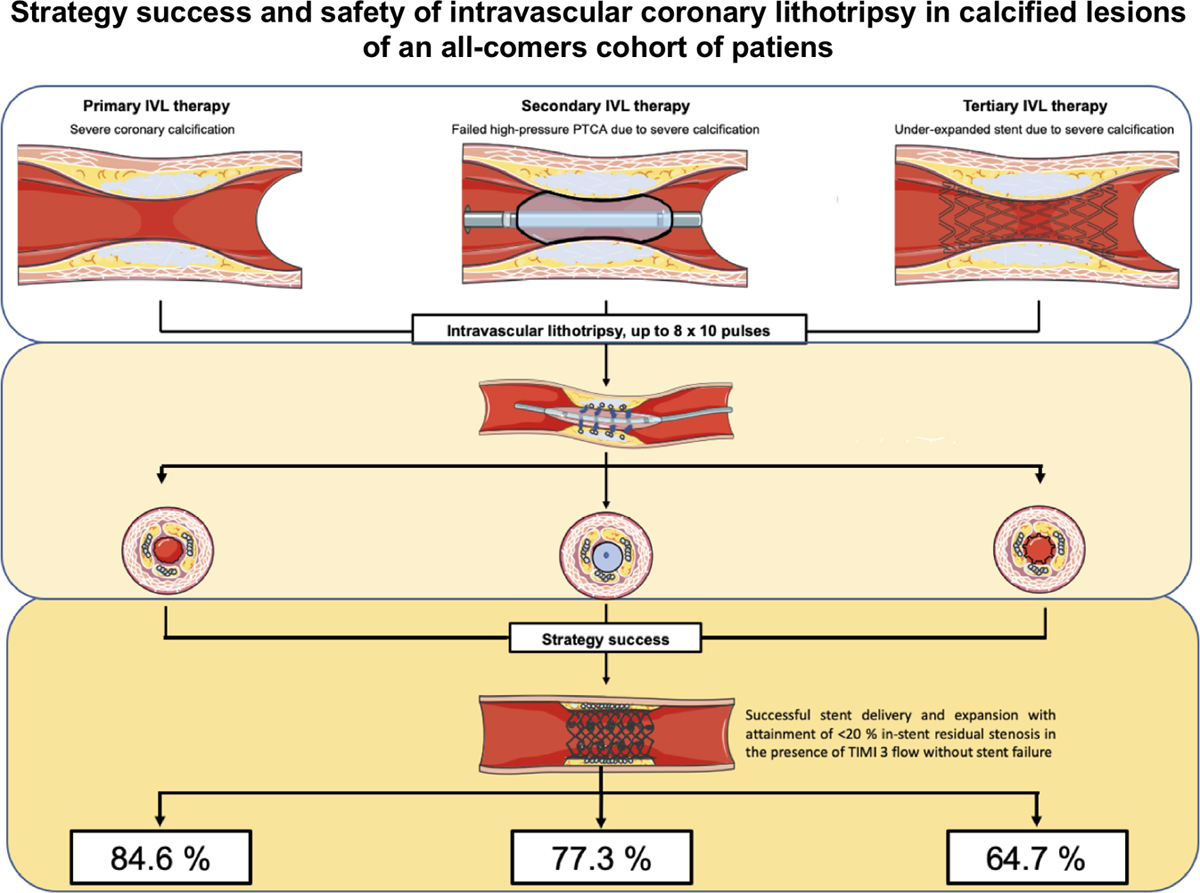

However, doctors may recommend more immediate treatments for severe coronary artery calcification. This may involve using special devices to remove calcifications and plaques from the arteries.

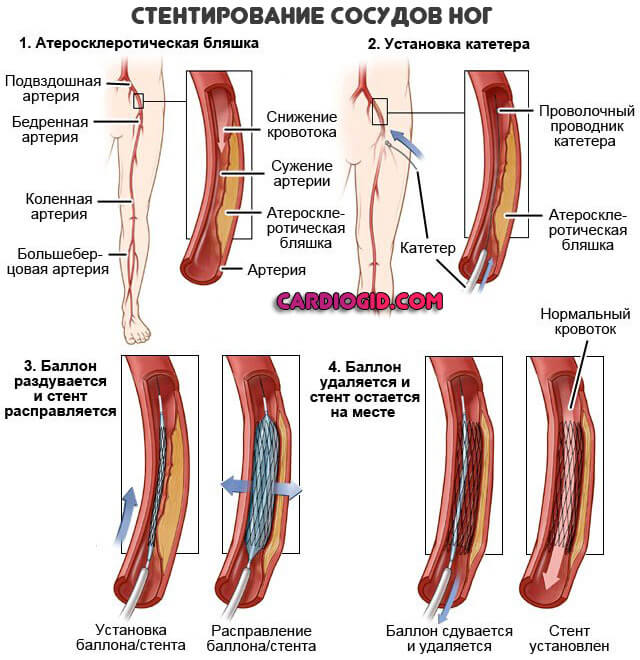

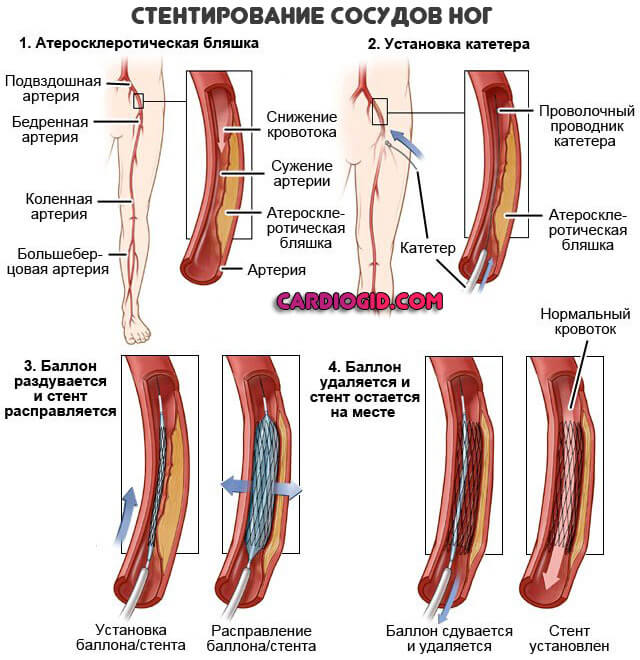

One such treatment is intravascular lithotripsy. This new approach involves threading a catheter to the coronary arteries and using a special device that breaks up the calcium in the arteries. After eliminating the calcium, a doctor will insert a stent into the coronary artery to keep the artery open so that blood can flow more easily.

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle and managing chronic health conditions can help reduce your risk of coronary artery calcifications. Examples of risk reduction techniques include:

- taking medications to reduce high blood pressure

- taking medications to reduce high cholesterol

- reducing dietary cholesterol intake by avoiding high-fat foods, such as fried foods

- managing diabetes, if you have it

Heart-healthy habits, including a low-fat diet and exercise, can help reduce your risk of calcifications and other chronic health conditions.

The presence of coronary artery calcifications increases your risk of heart problems. Their effects include:

- reduced blood flow to the heart

- reduced elasticity in your arteries

- higher pressures in the heart’s blood vessels

Severe CAD with calcifications increases your risk of cardiovascular events, such as a heart attack.

With early treatment and lifestyle modifications, you can help to lower your risk for more serious complications.

The following are some commonly asked questions regarding coronary artery calcification.

Can too much vitamin D cause coronary artery calcification?

Vitamin D is a vitamin found in some foods. Your body also creates it when you expose your skin to sunlight. The body needs vitamin D to be able to absorb calcium.

Animal studies have connected excess vitamin D supplementation with a higher risk of calcium deposits in the arteries. But researchers don’t yet know if excess vitamin D causes coronary artery calcification in humans.

Can calcium supplements cause coronary artery calcification?

Your body works to maintain appropriate calcium levels so you can have healthy teeth and bones. Taking calcium supplements can increase your body’s calcium levels so significantly that your body may have a harder time adjusting.

A large, long-term study identified a link between calcium supplementation and coronary artery calcification. The use of calcium supplements increased the risk of calcification. However, calcium intake can decrease the long-term risk for atherosclerosis, which can have a protective effect on your heart.

Can you reverse calcification in your arteries?

Reversing calcification in your arteries is a complicated topic. Most of the time, you likely won’t be able to reduce calcification without surgical interventions. However, you can choose lifestyle measures that prevent it from building up more.

Can calcified arteries be stented?

Calcified coronary arteries can be more difficult for a doctor to stent. Stenting is an approach to help open blood vessels that have become too narrow. A doctor may have difficulty getting a stent through because of the calcium.

Stenting is an approach to help open blood vessels that have become too narrow. A doctor may have difficulty getting a stent through because of the calcium.

If this is the case, they can use special kinds of stents, balloons, or lasers that help move through or remove the calcium.

Do statins prevent calcification?

Statin medications are cholesterol-lowering drugs that also can reduce plaque buildup from atherosclerosis. Medication examples include atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin.

Studies are conflicting about if statins also help to reduce coronary artery calcifications. However, statins do help to reduce the risk of coronary events, such as heart attacks.

Coronary artery calcification can be a sign that you have atherosclerosis and heart disease. A CT scan can help your doctor determine the extent of calcifications and recommend interventions.

If your doctor diagnoses coronary artery calcifications, you can take steps to prevent further buildup. It’s important to follow any recommended lifestyle measures and manage any underlying conditions.

It’s important to follow any recommended lifestyle measures and manage any underlying conditions.

Ryazan State Medical University named after Academician I.P. Pavlov

Ryazan State Medical University named after academician I.P. Pavlov – official site

Admission Committee +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Admission Committee +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Admission Committee +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Admission Committee +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Admissions office +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Reception Committee +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Reception Committee +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Reception Committee +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Admission Committee +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Admission Committee +7 (4912) 97-18-48

Additional professional education (4912) 97-18-37

Additional professional education (4912) 97- 18-37

Additional professional education (4912) 97-18-37

Additional professional education (4912) 97-18-37

Additional professional education (4912) 97-18-37

Additional professional education (4912) 97-18-37

Additional professional education (4912) 97-18-37

Additional e professional education (4912) 97-18-37

Additional professional education (4912) 97-18-37

Additional professional education (4912) 97-18-37

University in rankings

University in rankings

University in rankings

University in rankings

University in rankings

University in rankings

University in rankings

University in rankings

University in rankings

9000 2 University in rankings

Science news in Ryazan State Medical University

Science news in RyazGMU

Science news in RyazGMU

Science news in RyazGMU

Science news in RyazGMU

Science news in RyazGMU

Science news at RyazSMU

Science news at RyazSMU

Science news at RyazSMU

Science news at RyazSMU

05/30/2023

Admission Campaign – 2023

On our website in the section Home / Applicants / Applicants (specialist / bachelor / master) there is a video that details the rules for admission to Ryazan State Medical University.

05/25/2023

Intensive courses to prepare for entrance examinations

We invite you, dear applicants, to take intensive courses to prepare for the entrance exams, conducted by the university itself.

29.06.2023

The rector of the Ryazan State Medical University joined the Council for the quality of life

The Council was created under the Governor of the Ryazan region. The corresponding order was signed by the head of the region Pavel Viktorovich Malkov.

06/29/2023

The graduation of dentists took place in the Ryazan State Medical University

In practical healthcare, 112 graduates will begin their duties.

06/28/2023

Ready to go

Graduation at the Faculty of Preventive Medicine was held at the Ryazan State Medical University on June 27.

06/28/2023

Medical Student Squad

RyazGMU students will spend their holidays working as junior medical staff.

06/28/2023

On June 27, the sixth graduation of students of the pediatric faculty of the Ryazan State Medical University took place

Diplomas were received by 68 future doctors who will be able to work in polyclinics and hospitals in a month.

06/28/2023

“Active longevity – “Healthy Ryazan”

Ryazan State Medical University organized one of the sites at the opening of the regional project “Active Longevity – Healthy Ryazan”.

06/28/2023

Dictation about the history of RyazGMU

More than 200 people met at a dictation dedicated to the history of the university. Participants had to answer 51 questions in 40 minutes. After the end of the time allotted for work, the employees of the Center for the Development of Education of the Ryazan State Medical University analyzed the correct answers.

06/27/2023

Springboard to Science – 2023

Ryazan State Medical University student winner of the All-Russian Festival of Youth Science “Springboard to Science – 2023”

News

14. 02.2023

02.2023

TELL YOU WHO IS ALREADY AVAILABLE ONLINE TUITION PAYMENT IN RYAZGMU

Now all students of the FDPO RyazGMU can pay for training without leaving their homes. You can pay online and without commission using the new service pay.rzgmu.ru

09/23/2022

News FDPO RyazGMU

04/04/2023

Course “PSYCHOLOGICAL METHODS OF WORK WITH THE CONSEQUENCES OF PSYCHOTRAUFUL EVENTS”

Additional professional advanced training program “Psychological methods of working with the consequences of traumatic events” was developed for specialists with a psychological education.

02/28/2023

SWIMMING IN THE MEDICAL SENSE IS USEFUL FOR ABSOLUTELY EVERYONE

Why – says Valery Grigorievich Demikhov, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Director of the Scientific and Clinical Center for Hematology, Oncology and Immunology, Ryazan State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia

22. 02.2023

02.2023

DEPARTURE TO THE NOVOMOSKOVSK CITY CLINICAL HOSPITAL

On February 16, a visit to the State Healthcare Institution “Novomoskovsk City Clinical Hospital” took place. On behalf of the Ministry of Health of the Tula region, tests were prepared to assess the knowledge of obstetrician-gynecologists. Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Ryazan State Medical University Kovalenko M.S. and Dean of the FDPO RyazGMU Maksimtseva E.A. tested 21 specialists of the State Healthcare Institution “NGCH” and conducted a clinical tour of the departments of branch No. 2 of the State Health Institution “NGCH” together with the Deputy Chief Physician for Obstetrics and Gynecology Breus E.V. and department staff.

22.02.2023

TRAINING UNDER THE PROGRAM “NURSING IN PEDIATRICS” IS COMPLETED

On February 16, the 144-hour advanced training program “Nursing in Pediatrics” ended. During the training, nurses in the Ryazan region improved their knowledge and skills in nursing care for a healthy and sick child with infectious and somatic pathology, prevention of somatic and infectious pathology in childhood in accordance with the regulatory framework, professional standards and clinical recommendations.

During the training, nurses in the Ryazan region improved their knowledge and skills in nursing care for a healthy and sick child with infectious and somatic pathology, prevention of somatic and infectious pathology in childhood in accordance with the regulatory framework, professional standards and clinical recommendations.

02/16/2023

WetLab

02/14/2023

BASIC EMERGENCY FIRST AID COURSE

02/14/2023

COURSE “METHODS OF NON-TEST PSYCHODIAGNOSIS OF PERSONALITY”

27. 09.2022

09.2022

Russian as a foreign language (speech practice course)

FDPO

06/20/2023

INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION IN CHILDREN OVER THE NEWBORN PERIOD

Dear Colleagues! We invite you to the scientific and educational school “Intestinal obstruction in children older than the neonatal period”, which will be held on June 23, 2023. The event will discuss topical issues of diagnosis, treatment and tactics of the surgeon in intestinal obstruction in children.

06/20/2023

SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL CONFERENCE

High-profile specialists in the field of neonatology and obstetrics will make presentations on June 23, 2023 at the Ryazan State Medical University.

06/15/2023

Learning to write dissertations

The Council of Young Scientists of the Ryazan State Medical University will hold a meeting for graduate students, applicants and young scientists with Doctor of Medical Sciences Professor Elena Nikolaevna Yakusheva

09. 06.2023

06.2023

Conference of psychologists

We invite you to take part in the student scientific and practical conference “Formation of professional research competence of future clinical psychologists”

06/02/2023

I Congress of Therapists of the Central Federal District

8-9June at the Ryazan State Medical University will host a forum focused on practical healthcare professionals. The organizers are RNMOT, the Ministry of Health of the Ryazan Region and the Ryazan State Medical University.

06/02/2023

In June, the second cycle of training “Fundamentals of Kinesiology Taping” starts

The cycle is intended for everyone, regardless of the presence or absence of a medical education. Listeners have the opportunity to get or improve the skill of using elastic bands, to learn everything or almost everything about teips!

Listeners have the opportunity to get or improve the skill of using elastic bands, to learn everything or almost everything about teips!

29.05.2023

Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine in Pediatrics

On June 3, 2023, the University will host the Interregional Scientific and Practical Conference “Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine in Pediatrics”. Beginning at 10.00 in the hall of the Academic Council, at the address: Ryazan, st. Vysokovoltnaya, d. 7, bldg. 1, 4th floor.

05/25/2023

Mental health service: achievements and prospects

We invite you to take part in the IX Interregional Scientific and Practical Conference “Mental Health Service: Achievements and Prospects. Dedicated to the 135th anniversary of the Ryazan Regional Clinical Psychiatric Hospital. N.N. Bazhenov”, which will be held on June 2, 2023 on the basis of the Ryazan Regional Clinical Psychiatric Hospital. Bazhenova N.N.

Dedicated to the 135th anniversary of the Ryazan Regional Clinical Psychiatric Hospital. N.N. Bazhenov”, which will be held on June 2, 2023 on the basis of the Ryazan Regional Clinical Psychiatric Hospital. Bazhenova N.N.

05/22/2023

WE INVITE YOU TO READ THE PROGRAM OF THE CONFERENCE “TOPICAL ISSUES OF THERAPY AND GENERAL MEDICAL PRACTICE”

05/18/2023

To the attention of graduates, students and residents!

The annual large-scale event at the Ryazan Medical University – Job Fair 2023 – will be held on Tuesday, May 23 at 11 am in the foyer of the first and second floors of the medical and preventive building (Vysokovoltnaya st. , 7 building 1)!

, 7 building 1)!

Announcements

Lumbar disc herniation

Old, partially calcified disc herniation of the lumbar spine at the L4-5 level on the right, with foot paresis. Due to the defect, the foot slaps when walking and does not rise up. In the process of treatment with conservative methods, there is a significant improvement in the pain syndrome with the remaining weakness of the foot on the right.

Patient:

Male, 42 years old, Russia, St. Petersburg

Doctor:

Dr. Andrey Bitter, Neuwerk Clinic

Response of the spinal surgeon, Dr. Andrey Bitter

level 4 and 5th lumbar vertebrae on the right. It is she who clamps the 5th lumbar root and causes paresis of the foot. The operation is definitely needed, because. there was a slapping foot. I am not sure if the recovery of the foot will go quickly, but the pain in the lower part of the lumbar radiating to the leg should go away immediately after the operation. First of all, the patient needs to decompress the nerve root by removing the hernia.

First of all, the patient needs to decompress the nerve root by removing the hernia.

Patient questions

I was offered several treatment options, including endoscopic nucleoplasty and hernia repair with an anterior dynamic or static fixator. What type of operation do you offer?

Doctor’s answer

It seems that the changes are not quite fresh, ie. it is possible that the hernia already has a partially ossified structure. These hernias are best removed microscopically rather than endoscopically. The nucleoplasty method is not applicable here, because. sequestered hernia, i.e. out of the disk.

Since the patient has multiple changes in the form of protrusion of discs and osteochondrosis of almost the entire lumbar region, some hotheads will want to “prophylactically” insert screws so that a repeated hernia does not allegedly occur. Indeed, it will not occur in this department, but neighboring segments will be prone to increased load due to additional restriction in movement and will begin to wear out more quickly, which will lead, in about 5–10 years, to a repeated large operation.

I strongly recommend that you limit yourself to a minimal solution to the problem and watch further developments. The installation of a disc prosthesis is contraindicated here, because. too much change in the facet joints. In addition, anterior access (through the abdomen) in men may be accompanied by a violation of ejaculation after surgery, not to mention the possibility of damage to the vessels (aorta), i.e. the risk is not justified. In this case, the criteria for fitting a prosthesis are not met.

Estimated cost of treatment: 8.200 Euro

Treatment

A microsurgical operation was performed to remove part of a heavily ossified disc herniation and neurolysis (decompression) of the 5th lumbar root on the right.

The postoperative period was uneventful. Mobilization of the patient and removal of the drain occurred the next day after the operation. The patient was discharged on the 6th day after the operation.

If severe paresis of the right foot persists, it is recommended to temporarily wear a splint that keeps the foot in flexion, which will reduce the risk of sudden dislocation or fracture of the foot, as well as further physiotherapy and gymnastics of the muscles of the leg and foot.

This is usually due to atherosclerosis.

This is usually due to atherosclerosis.