Old fashioned measles. The Comprehensive History of Measles: From Ancient Times to Modern Eradication Efforts

When was measles first documented. How did the measles vaccine development unfold. What were the major milestones in measles elimination efforts. How does the measles virus manifest in infected individuals. What are the key symptoms and stages of measles infection.

The Origins and Early Documentation of Measles

Measles, a highly contagious viral disease, has plagued humanity for centuries. Its earliest documented mention dates back to the 9th century when a Persian physician provided one of the first written accounts of the disease. This early recognition highlights the long-standing impact of measles on human populations.

In 1757, a significant breakthrough occurred when Francis Home, a Scottish doctor, demonstrated that measles was caused by an infectious agent present in the blood of patients. This discovery laid the groundwork for future research and understanding of the disease’s transmission.

Measles in the Pre-Vaccine Era

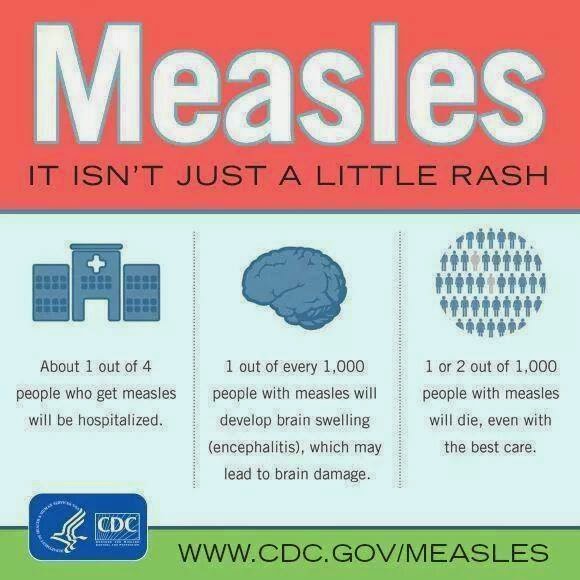

Before the advent of vaccination, measles was a ubiquitous childhood illness. In the United States alone, it is estimated that 3 to 4 million people were infected annually in the decade preceding 1963. The disease’s impact was severe:

- 400 to 500 deaths reported each year

- 48,000 hospitalizations

- 1,000 cases of encephalitis (brain swelling)

These statistics underscore the devastating toll measles took on public health before effective prevention methods were developed.

The Development of the Measles Vaccine

The turning point in the fight against measles came with the development of a vaccine. This process began in 1954 when John F. Enders and Dr. Thomas C. Peebles collected blood samples from ill students during a measles outbreak in Boston, Massachusetts.

The Edmonston Strain: A Breakthrough in Vaccine Research

Enders and Peebles successfully isolated the measles virus from the blood of a 13-year-old student named David Edmonston. This strain, known as the Edmonston strain, became the foundation for the first measles vaccine.

In 1963, Enders and his colleagues transformed the Edmonston-B strain into a vaccine, which was subsequently licensed for use in the United States. This marked a pivotal moment in the history of measles prevention.

Refinement and Improvement of the Vaccine

Five years later, in 1968, Maurice Hilleman and his team developed an improved and weaker version of the measles vaccine. This refined vaccine, based on the Edmonston-Enders strain (formerly known as “Moraten”), has been the sole measles vaccine used in the United States since its introduction.

Today, the measles vaccine is typically administered in combination with vaccines for mumps and rubella (MMR) or with mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV). This approach has greatly simplified immunization schedules and improved overall vaccination rates.

Efforts Towards Measles Elimination

The introduction of the measles vaccine marked the beginning of a concerted effort to eliminate the disease. In 1978, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) set an ambitious goal to eliminate measles from the United States by 1982.

Progress and Challenges in Measles Elimination

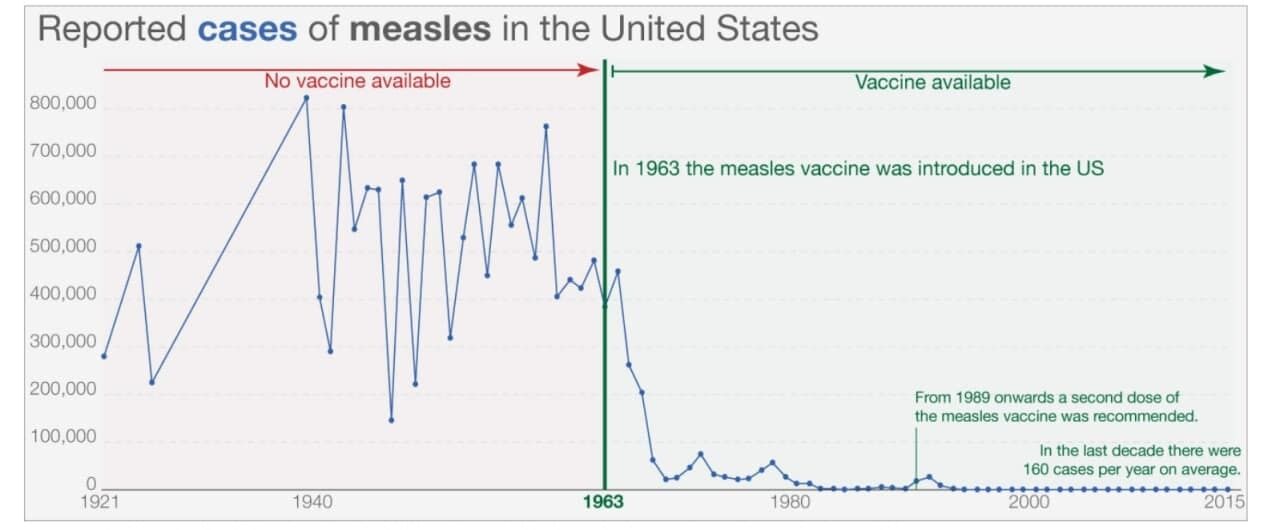

While the 1982 goal was not met, the widespread use of the measles vaccine led to a dramatic reduction in disease rates. By 1981, reported measles cases had decreased by 80% compared to the previous year. However, challenges remained.

A series of measles outbreaks among vaccinated school-aged children in 1989 prompted a reassessment of vaccination strategies. In response, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommended a second dose of the MMR vaccine for all children.

Achieving Elimination Status

The implementation of the two-dose recommendation, coupled with improvements in first-dose MMR vaccine coverage, led to a further decline in reported measles cases. In 2000, measles was declared eliminated from the United States, marking the absence of continuous disease transmission for more than 12 months.

This achievement was the result of a highly effective vaccination program in the United States and improved measles control throughout the Americas region. It stands as a testament to the power of coordinated public health efforts and widespread immunization.

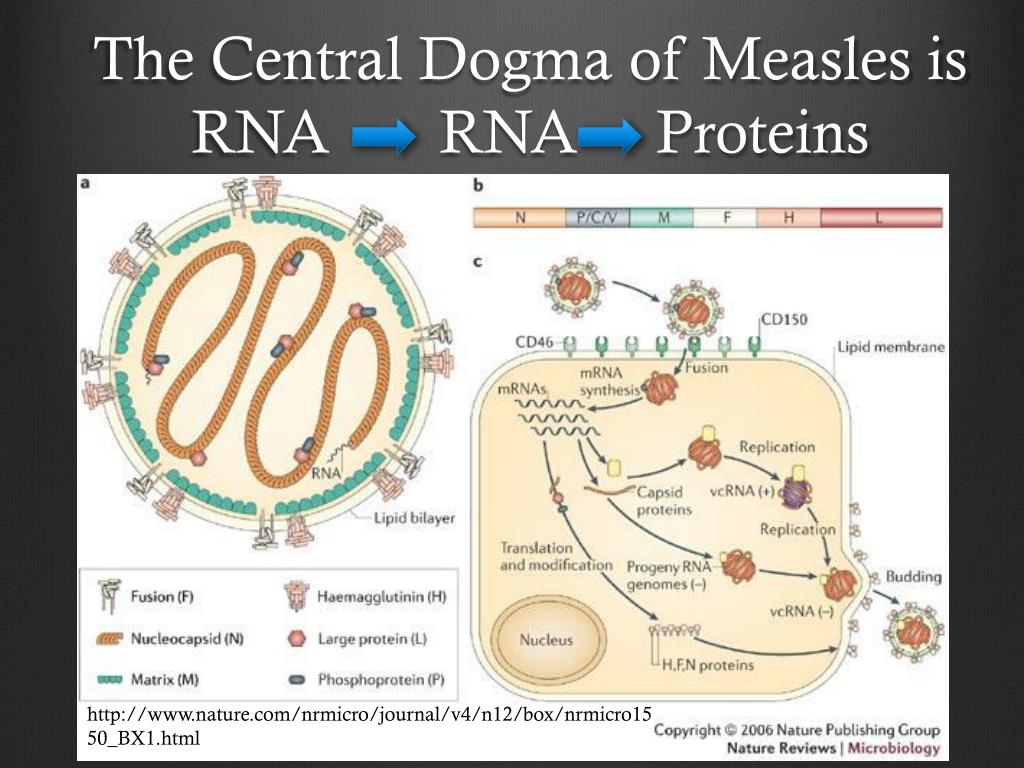

Understanding Rubeola: The Measles Virus

Rubeola, commonly known as measles, is an infection caused by a virus that proliferates in the cells lining the throat and lungs. Its highly contagious nature is due to its ability to spread through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

Transmission and Incubation Period

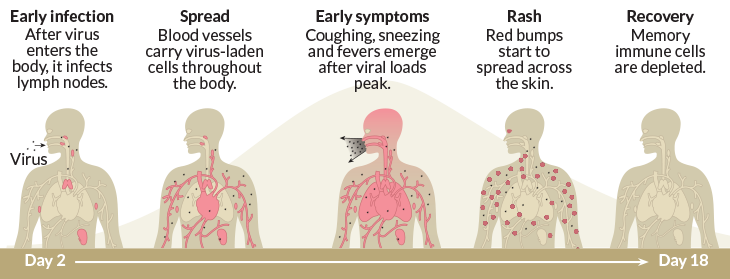

The measles virus is exceptionally contagious. After exposure, it typically takes 7 to 14 days for the first symptoms to appear. This period, known as the incubation period, is crucial for understanding the spread of the disease.

Initial Symptoms of Measles

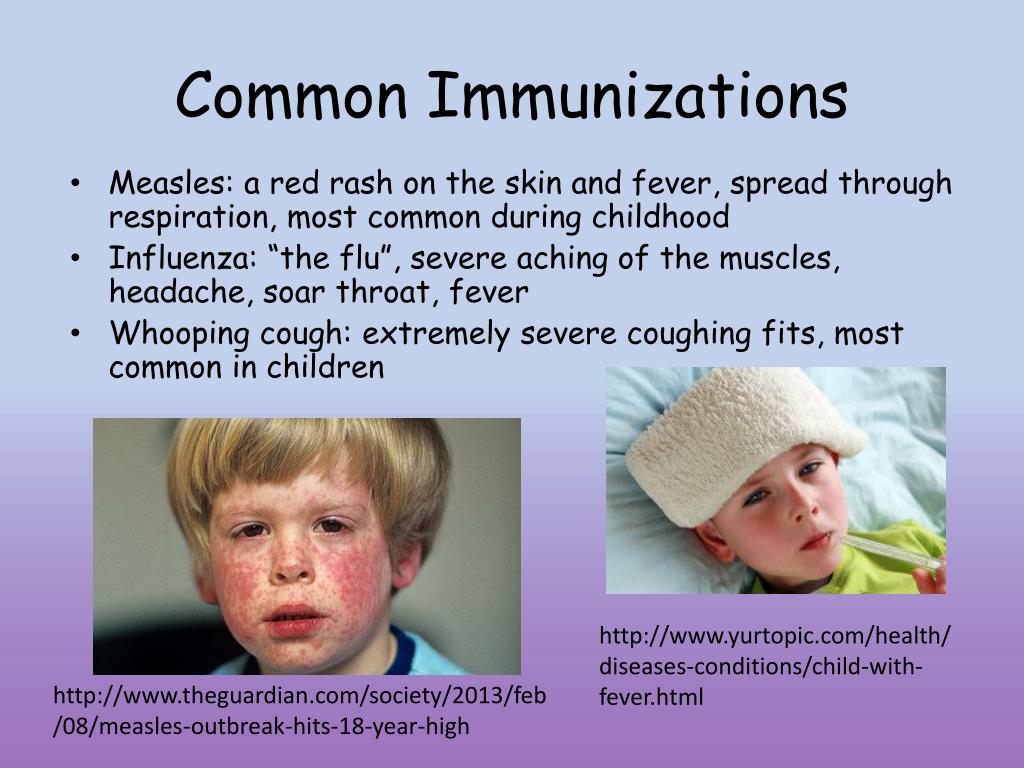

The early stages of measles infection often mimic a cold or flu. Common initial symptoms include:

- Fever

- Cough

- Runny nose

- Sore throat

- Red and runny eyes

These symptoms typically last for several days before the characteristic measles rash appears.

The Progression of Measles: From Koplik’s Spots to Rash

As measles progresses, it manifests in distinct stages, each with its own set of symptoms and characteristics.

Koplik’s Spots: An Early Indicator

Two to three days after the initial symptoms appear, tiny spots may develop inside the mouth, particularly on the cheeks. These spots, known as Koplik’s spots, are usually red with blue-white centers. Named after pediatrician Henry Koplik, who first described them in 1896, these spots are considered a hallmark of early measles infection.

Koplik’s spots typically fade as other measles symptoms intensify, serving as a valuable diagnostic tool for healthcare providers.

The Characteristic Measles Rash

The most recognizable feature of measles is its distinctive rash. This rash typically appears 3 to 5 days after the initial symptoms and is characterized by:

- Red or reddish-brown coloration

- Progression from the face downward

- Coverage of the entire body within a few days

The rash begins on the face and gradually spreads to the neck, trunk, arms, legs, and finally, the feet. It consists of blotches of colored bumps that can merge as they spread across the body. The rash typically lasts for five to six days before beginning to fade.

It’s important to note that immunocompromised individuals might not develop the characteristic rash, making diagnosis more challenging in these cases.

Complications and Treatment of Measles

While measles is often considered a childhood disease, it can lead to serious complications, particularly in vulnerable populations such as young children, pregnant women, and individuals with compromised immune systems.

Potential Complications

If left untreated, measles can result in various complications, including:

- Ear infections

- Pneumonia

- Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain)

These complications underscore the importance of proper medical care and monitoring during measles infection.

Treatment Approaches

There is no specific antiviral treatment for measles. Management typically focuses on supportive care to alleviate symptoms and prevent complications. This may include:

- Rest and hydration

- Fever-reducing medications

- Vitamin A supplementation (in certain cases)

In some instances, administering the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine within the first three days after exposure to the virus may prevent the disease or reduce its severity. However, this approach is not always effective and should be done under medical supervision.

The Importance of Vaccination in Measles Prevention

The development and widespread implementation of the measles vaccine have been pivotal in reducing the global burden of this disease. Vaccination remains the most effective strategy for preventing measles outbreaks and protecting individuals and communities.

Herd Immunity and Its Significance

Herd immunity plays a crucial role in measles prevention. When a high percentage of a population is vaccinated, it becomes difficult for the virus to spread, indirectly protecting those who cannot be vaccinated due to age or medical conditions.

To achieve herd immunity against measles, approximately 95% of the population needs to be vaccinated. This high threshold is due to the extremely contagious nature of the virus.

Challenges to Measles Elimination

Despite the availability of an effective vaccine, measles elimination efforts face several challenges:

- Vaccine hesitancy and misinformation

- Gaps in healthcare access in certain regions

- Importation of cases from areas where measles is still endemic

Addressing these challenges requires ongoing public health efforts, education, and global cooperation to maintain high vaccination rates and prevent resurgence of the disease.

The Future of Measles Control and Eradication

While significant progress has been made in controlling measles, the goal of global eradication remains elusive. Continued vigilance and coordinated efforts are necessary to build upon past successes and overcome current challenges.

Ongoing Research and Development

Scientists and public health experts continue to work on improving measles prevention and control strategies. Areas of focus include:

- Developing new vaccine delivery methods

- Improving vaccine stability for use in challenging environments

- Enhancing surveillance systems to detect outbreaks early

Global Cooperation and Initiatives

International organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF are spearheading global initiatives to eliminate measles. These efforts involve:

- Coordinating vaccination campaigns in high-risk areas

- Providing technical support to countries for measles control programs

- Facilitating knowledge sharing and best practices among nations

The journey from the first documented cases of measles to the current state of near-elimination in many parts of the world is a testament to the power of scientific research, public health initiatives, and global cooperation. As we continue to face challenges in measles control, the lessons learned from this history provide valuable insights for future efforts in disease prevention and eradication.

History of Measles | CDC

Pre-vaccine era

In the 9th century, a Persian doctor published one of the first written accounts of measles disease.

Francis Home, a Scottish physician, demonstrated in 1757 that measles is caused by an infectious agent in the blood of patients.

In 1912, measles became a nationally notifiable disease in the United States, requiring U.S. healthcare providers and laboratories to report all diagnosed cases. In the first decade of reporting, an average of 6,000 measles-related deaths were reported each year.

In the decade before 1963 when a vaccine became available, nearly all children got measles by the time they were 15 years of age. It is estimated 3 to 4 million people in the United States were infected each year. Also each year, among reported cases, an estimated 400 to 500 people died, 48,000 were hospitalized, and 1,000 suffered encephalitis (swelling of the brain) from measles.

Vaccine development

In 1954, John F. Enders and Dr. Thomas C. Peebles collected blood samples from several ill students during a measles outbreak in Boston, Massachusetts. They wanted to isolate the measles virus in the student’s blood and create a measles vaccine. They succeeded in isolating measles in 13-year-old David Edmonston’s blood.

Enders and Dr. Thomas C. Peebles collected blood samples from several ill students during a measles outbreak in Boston, Massachusetts. They wanted to isolate the measles virus in the student’s blood and create a measles vaccine. They succeeded in isolating measles in 13-year-old David Edmonston’s blood.

In 1963, John Enders and colleagues transformed their Edmonston-B strain of measles virus into a vaccine and licensed it in the United States. In 1968, an improved and even weaker measles vaccine, developed by Maurice Hilleman and colleagues, began to be distributed. This vaccine, called the Edmonston-Enders (formerly “Moraten”) strain has been the only measles vaccine used in the United States since 1968. Measles vaccine is usually combined with mumps and rubella (MMR), or combined with mumps, rubella and varicella (MMRV). Learn more about measles vaccine.

Measles elimination

In 1978, CDC set a goal to eliminate measles from the United States by 1982. Although this goal was not met, widespread use of measles vaccine drastically reduced the disease rates. By 1981, the number of reported measles cases was 80% less compared with the previous year. However, a 1989 measles outbreaks among vaccinated school-aged children prompted the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) to recommend a second dose of MMR vaccine for all children. Following widespread implementation of this recommendation and improvements in first-dose MMR vaccine coverage, reported measles cases declined even more.

By 1981, the number of reported measles cases was 80% less compared with the previous year. However, a 1989 measles outbreaks among vaccinated school-aged children prompted the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) to recommend a second dose of MMR vaccine for all children. Following widespread implementation of this recommendation and improvements in first-dose MMR vaccine coverage, reported measles cases declined even more.

Measles was declared eliminated (absence of continuous disease transmission for greater than 12 months) from the United States in 2000. This was thanks to a highly effective vaccination program in the United States, as well as better measles control in the Americas region. For more information, see Frequently Asked Questions about Measles in the U.S.

To read more about the history of vaccines, see History of Vaccines: Measles Timeline.

What Does Rubeola (Measles) Look Like?

What is rubeola (measles)?

Rubeola (measles) is an infection caused by a virus that grows in the cells lining the throat and lungs. It’s a very contagious disease that spreads through the air whenever someone who is infected coughs or sneezes. People who catch the measles develop symptoms such as a fever, cough, and runny nose. A telltale rash is the hallmark of the disease. If measles isn’t treated, it can lead to complications such as ear infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain).

It’s a very contagious disease that spreads through the air whenever someone who is infected coughs or sneezes. People who catch the measles develop symptoms such as a fever, cough, and runny nose. A telltale rash is the hallmark of the disease. If measles isn’t treated, it can lead to complications such as ear infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain).

Within seven to 14 days after getting infected with the measles, your first symptoms will appear. The earliest symptoms feel like a cold or the flu, with a fever, cough, runny nose, and sore throat. Often the eyes get red and runny. Three to five days later, a red or reddish-brown rash forms and spreads down the body from head to foot.

Koplik’s spots

Two to three days after you first notice measles symptoms, you may start to see tiny spots inside the mouth, all over the cheeks. These spots are usually red with blue-white centers. They’re called Koplik’s spots, named for pediatrician Henry Koplik who first described the early symptoms of measles in 1896. Koplik’s spots should fade as the other measles symptoms disappear.

Koplik’s spots should fade as the other measles symptoms disappear.

The measles rash

The measles rash is red or reddish-brown in color. It starts on the face and works its way down the body over a few days: from the neck to the trunk, arms, and legs, until it finally reaches the feet. Eventually, it will cover the entire body with blotches of colored bumps. The rash lasts for five or six days in total. Immunocompromised people might not have the rash.

Share on Pinterest

There isn’t any real treatment for measles. Sometimes getting the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine within the first three days after being exposed to the virus can prevent the disease.

The best advice for people who are already sick is to rest and give the body time to recover. Stay comfortable by drinking plenty of fluids and taking acetaminophen (Tylenol) for fever. Don’t give aspirin to children, because of the risk for a rare but serious condition called Reye’s syndrome.

About 30 percent of people who get the measles develop complications such as pneumonia, ear infections, diarrhea, and encephalitis, according to the CDC. Pneumonia and encephalitis are two severe complications that could require hospitalization.

Pneumonia and encephalitis are two severe complications that could require hospitalization.

Pneumonia

Share on Pinterest

Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs that causes:

- fever

- chest pain

- trouble breathing

- cough that produces mucus

People whose immune system has been weakened by another disease can get an even more dangerous form of pneumonia.

Encephalitis

Share on Pinterest

About one out of every 1,000 children with measles will develop swelling of the brain called encephalitis, according to the CDC. Sometimes encephalitis starts right after the measles. In other cases, it takes months to emerge. Encephalitis can be very serious, leading to convulsions, deafness, and mental retardation in children. It’s also dangerous for pregnant women, causing them to give birth too early or to have a baby born underweight.

Share on Pinterest

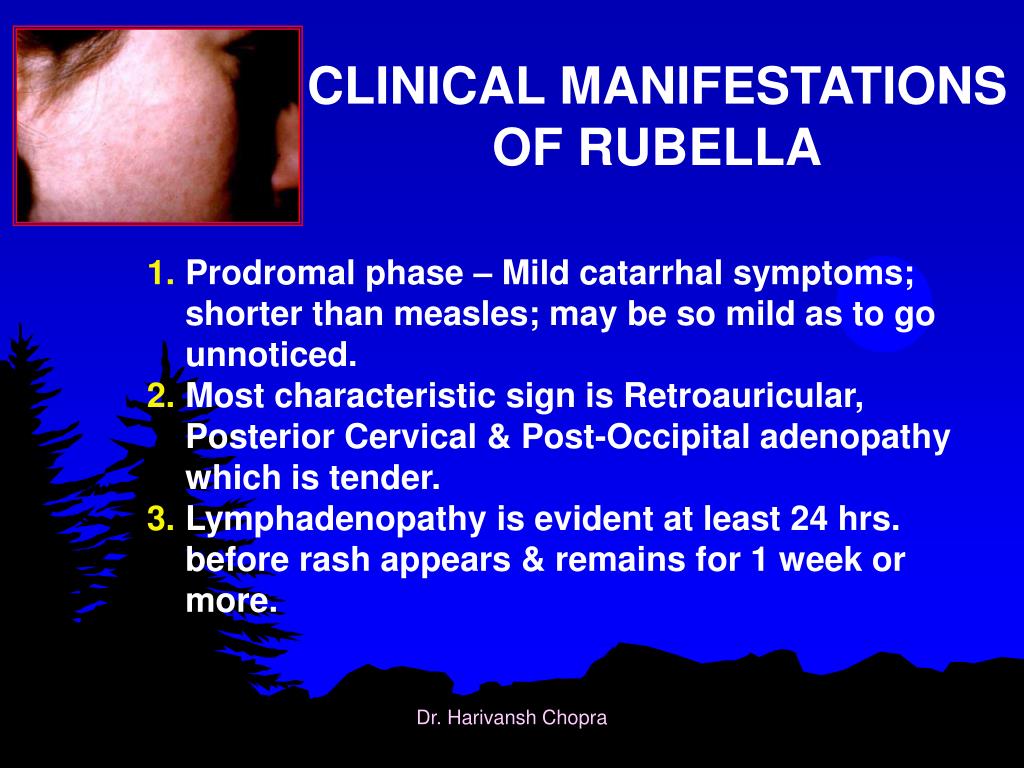

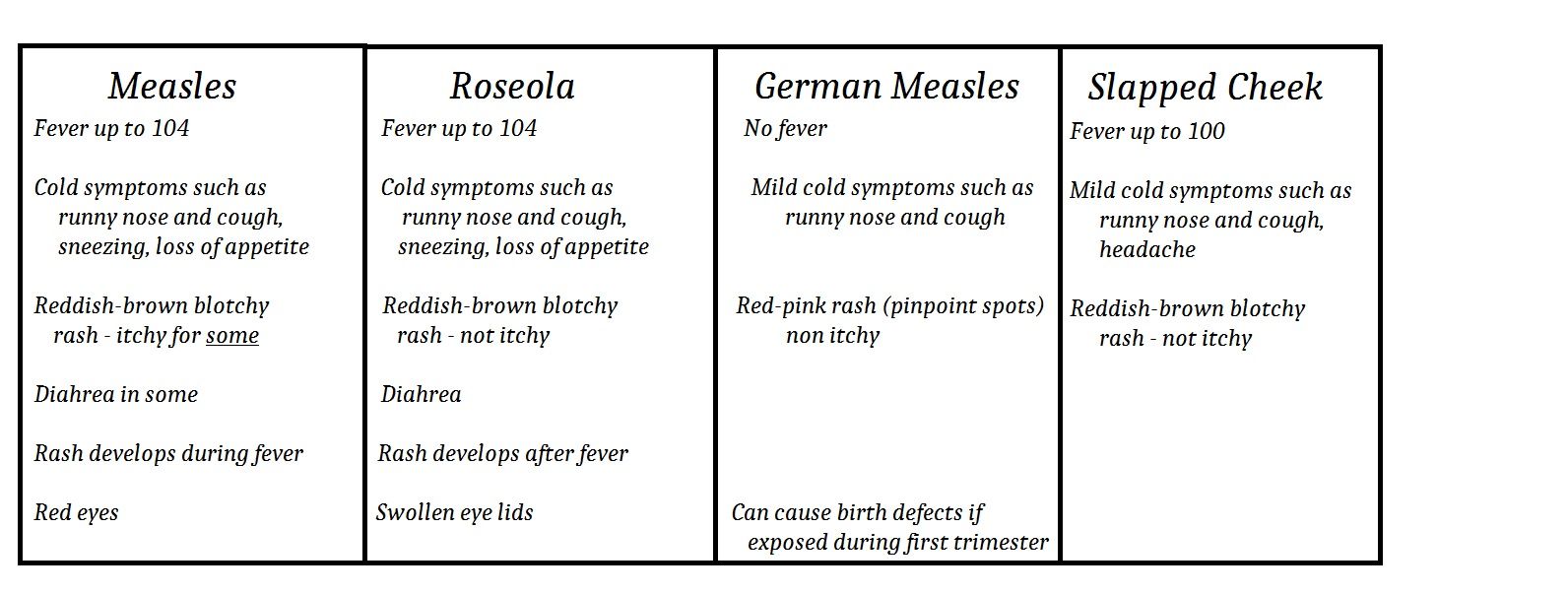

Rubeola (measles) is often confused with roseola and rubella (German measles), but these three conditions are different. Measles produces a splotchy reddish rash that spreads from head to foot. Roseola is a condition that affects infants and toddlers. It causes a rash to form on the trunk, which spreads to the upper arms and neck and fades within days. Rubella is a viral disease with symptoms including a rash and fever that last two to three days.

Measles produces a splotchy reddish rash that spreads from head to foot. Roseola is a condition that affects infants and toddlers. It causes a rash to form on the trunk, which spreads to the upper arms and neck and fades within days. Rubella is a viral disease with symptoms including a rash and fever that last two to three days.

Share on Pinterest

Symptoms of the measles often disappear in the same order in which they first emerged. After a few days, the rash should start to fade. It may leave behind a brownish color on the skin, as well as some peeling. The fever and other measles symptoms will recede and you — or your child should begin to feel better.

Did 90,000 people really bring the disease to the USA from Uman?

In early April, the American New York Times published an article about a measles outbreak in the United States. The publication suggested that measles could have entered the United States from Ukraine – Hasidim could have become infected when they traveled to Uman in September for the Jewish New Year Rosh Hashanah. Hromadsky’s journalist traveled to New York to find out if American measles really had a Ukrainian origin.

The publication suggested that measles could have entered the United States from Ukraine – Hasidim could have become infected when they traveled to Uman in September for the Jewish New Year Rosh Hashanah. Hromadsky’s journalist traveled to New York to find out if American measles really had a Ukrainian origin.

Hasidic New York

The Williamsburg area is the epicenter of the measles outbreak in New York. Over the past six months, more than 460 cases of the disease have been recorded in the city, most of them here. Williamsburg is a Jewish area. Its border runs clearly along certain streets. It’s like a separate world with its own laws.

Apart from the Hasidim, you will hardly meet anyone here. All adult men are dressed identically: black jackets, white shirts, old-fashioned shoes and characteristic Jewish hats. Women walk mostly with children – sometimes you can see five, six, or even seven children with their mother. Brothers and sisters are also often dressed in the same way.

The signs here are in Yiddish, a language that only Conservative Jews use. English is not heard on the streets either. Another detail that distinguishes this area from the world a few blocks away is that there are no smartphones here. This immediately catches the eye: people do not use iPhones, but old Nokias or Motorolas that were popular ten, if not more, years ago. Occasionally, smartphones allow businessmen to use them for work – but then a special application must be installed on the gadgets – a “kosher filter” that will block all sinful content. The Internet, like television, is a forbidden thing for Hasidim.

Mother with children in the Jewish neighborhood of Williamsburg in New York, USA, May 6, 2019

Ostap Yarysh/Hromadske

It can be assumed that vaccinations are also prohibited. But this is not so – religion allows Hasidim to be vaccinated. Therefore, the reason for the rapid spread of measles here is different.

Therefore, the reason for the rapid spread of measles here is different.

“Their families have an average of seven children,” says physician Josif Shalamon. He himself comes from Mukachevo, but has been working as a therapist in the United States for thirty years. His clinic is located in the Jewish district of New York, and most of the doctor’s patients are Hasidim.

“Where one child becomes infected, an uncle, aunt, brother, sister becomes infected. If ordinary families usually have two children, Hasidim can have 10-11. It seems to me that this plays a big role, since the main risk group is children.”

Indeed, if you look at the statistics of measles patients in New York, most of them are Jewish children under four years of age. Not all of them are vaccinated, although in fact most Jews are vaccinated, the doctor says. And those who refuse it do so for the same reasons as other opponents of vaccination.

Physician Josef Shalamon at the outpatient clinic in the Jewish district of New York, USA, May 6, 2019

Ostap Yarysh/Hromadske

Uman is not to blame

“I was in Uman three weeks ago and didn’t bring measles with me,” laughs Rabbi Yakov Cohen, who works in New York at the UN. — There is hardly any connection with Ukraine. We go there to pray – it’s always exciting, and I don’t think anyone could have brought measles from there.”

— There is hardly any connection with Ukraine. We go there to pray – it’s always exciting, and I don’t think anyone could have brought measles from there.”

While the link between the Hasidic outbreak and the epidemic in Ukraine seems logical at first glance, Dr. Shalamon is also skeptical.

“A person could just as well get measles in other places and from anyone,” says the doctor. — On the plane, at the airport, it is very easy to pick up viral diseases. Everything is very tight in there. Imagine a plane flies for 12-13 hours. People are in one closed space, without ventilation. They go to the toilet – who knows if they washed their hands after that. It is very difficult to track down the first person who contracted measles. And it is all the more difficult to track whether a person was in such and such a city, in Uman, whether he picked her up there. There are no guarantees here.”

Meanwhile, the American press continues to say that the measles is spreading because of the Hasidim, Somalis or diasporans from Eastern Europe. The Ukrainian Public Health Center says that it is impossible to blame one social group for the spread of the disease, because outbreaks of measles are now recorded in all countries of the world. And it is very difficult to prove exactly how and where exactly a person contracted measles.

The Ukrainian Public Health Center says that it is impossible to blame one social group for the spread of the disease, because outbreaks of measles are now recorded in all countries of the world. And it is very difficult to prove exactly how and where exactly a person contracted measles.

Moreover, last year the Hasidic holiday in Uman was in September. And although at the same time the first case of the disease was recorded in New York, the main outbreak occurred only in February-March, that is, almost six months later. Then the city authorities decided to take serious measures.

Residents of the Jewish neighborhood of Williamsburg in New York, USA, May 6, 2019

Ostap Yarysh/Hromadske

(Non)kosher quarantine

In April, the Mayor of New York declared a state of emergency and mandatory vaccinations in the Jewish areas of the city. Those who refuse to get vaccinated can now face a $1,000 fine. Previously, unvaccinated children were banned from attending schools, but this did not help much.

Those who refuse to get vaccinated can now face a $1,000 fine. Previously, unvaccinated children were banned from attending schools, but this did not help much.

“When I was little, not everyone was vaccinated—it wasn’t necessary. Everyone had been ill with measles or chickenpox – and that was normal. Some children were vaccinated, some were not,” Rabbi Yaakov Cohen shrugs. He considers the measures of the city authorities a violation of the rights of Jews.

“I am not in favor of compulsory vaccination, it is a personal matter for everyone. There are arguments for and arguments against, and I understand both positions. It is dangerous when we start to single out some group of people and focus on the fact that they are different. Especially when the media do it – and I’m talking about any group of people, not just Jews. It shouldn’t be.”

Residents of the Jewish neighborhood of Williamsburg in New York, USA, May 6, 2019

Ostap Yarysh/Hromadske

However, the New York City Council Health Department is convinced that the issue here is not discrimination at all, but normal medical measures. In Jewish districts, propaganda posters are put up with a call to go to the doctor. And on the main page of the department there is information about the measles outbreak, how to identify the symptoms, and where you can get the vaccine. Residents of Jewish areas, by the way, they are made here for free.

In Jewish districts, propaganda posters are put up with a call to go to the doctor. And on the main page of the department there is information about the measles outbreak, how to identify the symptoms, and where you can get the vaccine. Residents of Jewish areas, by the way, they are made here for free.

“My impression is that most Jews still take it seriously,” says Dr. Shalaman. “And although some Hasidim in Williamsburg came out to protest against mandatory vaccinations and fines, the information campaign had a positive effect on most people. Only today I had two patients who had slight redness on the skin, and they came to take tests. Luckily, they don’t have measles.”

***

In Ukraine, the measles epidemic began in 2017, peaking at the end of 2018. More than 53,000 Ukrainians fell ill with measles last year. From the beginning of 2019about 40,000 people fell ill with measles.

Measles vaccines are available in all state medical institutions and are free of charge for young people and everyone at risk: doctors, teachers, police, military and combatants in the Donbass.

Immigration and health issues are the main focus of the US Democratic Party televised debate

August 1, 2019, 04:34

NEW YORK, August 1st. /TASS/. The controversy on the most pressing topics – from the problems of illegal migration to health care, the “green” economy and the situation in Afghanistan – unfolded on Wednesday, on the final day of the second televised debate held in Detroit (Michigan) of the presidential contenders from the Democratic Party. The broadcast was hosted by CNN.

The unprecedented number of participants – 20 people – forced the Democratic National Committee to hold them in two stages. Last night, the top ten took to the stage of the Fox Theater Hall – Senator Bernie Sanders from Vermont and Senator Elizabeth Warren from Massachusetts, Congressman from Ohio Tim Ryan, Senator from Minnesota Amy Klobuchar, Mayor of South Bend (Indiana) Pete Buttejudzh , former Texas Congressman Beto O’Rourke, former Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper, former Maryland Congressman John Delaney, writer Marianne Williamson, and Montana Governor Steve Bullock, who replaced California Congressman Eric Swolwell, who participated in the first televised debate in June , who previously announced that he was withdrawing from the fight. Tuesday’s debate was watched by 8.7 million viewers and 2.8 million watched online, according to Nielsen Research Service. As The Hill newspaper recalled on Wednesday, the audience for the first Democratic televised debate in Miami on June 26 was significantly larger – 15.3 million people.

Tuesday’s debate was watched by 8.7 million viewers and 2.8 million watched online, according to Nielsen Research Service. As The Hill newspaper recalled on Wednesday, the audience for the first Democratic televised debate in Miami on June 26 was significantly larger – 15.3 million people.

On Wednesday evening, US Vice President Joseph Biden, New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, former US Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Julian Castro, and Tulsi Gabbard, member of the US House of Representatives from Hawaii, presented their views on US domestic and foreign policy. , New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, California Senator Kamala Harris, Washington Governor Jay Inslee, entrepreneur Andrew Young, Colorado Senator Michael Bennett, and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Biden-Harris duel

Even before the TV debate began, political observers called the Joe Biden-Kamala Harris tandem a “dream team” that the Democrats could field in the 2020 elections. However, during the first televised debate in June in Miami, Harris engaged in a hard clinch with former Vice President Biden, bombarding him with uncomfortable questions about segregation politics in the 1970s. On the eve of the current debate, CBS noted on Wednesday, Biden, who has 32% of Democrats in the latest RealClear Politics polls, vowed he would “not be overly polite” if he were again targeted by Harris, the level of support which grew noticeably and reached 10.8%.

On the eve of the current debate, CBS noted on Wednesday, Biden, who has 32% of Democrats in the latest RealClear Politics polls, vowed he would “not be overly polite” if he were again targeted by Harris, the level of support which grew noticeably and reached 10.8%.

However, upon entering the stage, Biden, 76, treated Harris with old-fashioned courtesy, jokingly calling her “baby” and asking her to be “softer” with him during the debate. This call was not heeded: the California senator immediately criticized Biden’s position on health and immigration issues. “We must all agree that access to health care should be seen as a right, not a privilege,” she said, defending her version of the Medicare For All health insurance system, while Biden considers health insurance reform to be quite effective, carried out during the administration of Barack Obama.

End the New Cold War and Withdraw Forces from Afghanistan

During the debate, only Tulsi Gabbard, a member of the U. S. House of Representatives from Hawaii, who served in the military in Iraq, touched on foreign policy issues in detail. “[U.S. President] Donald Trump is pursuing a belligerent policy that is not in our interests,” she said. “His actions are turning into an escalation of tensions with nuclear powers such as Russia and China, as well as North Korea, which is pushing us into a new cold war and to the very brink of nuclear catastrophe. Already, thousands of nuclear missiles are aimed at our country.”

S. House of Representatives from Hawaii, who served in the military in Iraq, touched on foreign policy issues in detail. “[U.S. President] Donald Trump is pursuing a belligerent policy that is not in our interests,” she said. “His actions are turning into an escalation of tensions with nuclear powers such as Russia and China, as well as North Korea, which is pushing us into a new cold war and to the very brink of nuclear catastrophe. Already, thousands of nuclear missiles are aimed at our country.”

She recalled that the flight time of nuclear missiles to the United States is only about 30 minutes. “If elected to the presidency, I will put an end to this madness,” she added. “This situation simply should not arise. to ease tensions that cost trillions of dollars and redirect these resources in a way that serves the needs of our people.”

Gabbard also promised to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan in her first year in the White House if she is elected president. The same position was expressed by Senator Cory Booker, who promised to “withdraw American troops from there as quickly as possible. ” “I will not set any arbitrary deadlines, but I will do it quickly and with due regard for security measures, and in such a way that there is no dangerous vacuum that is fraught with destabilization of the situation,” he added. Businessman Andrew Yang, in response to a question about Iran policy, called for a “de-escalation of tensions.”

” “I will not set any arbitrary deadlines, but I will do it quickly and with due regard for security measures, and in such a way that there is no dangerous vacuum that is fraught with destabilization of the situation,” he added. Businessman Andrew Yang, in response to a question about Iran policy, called for a “de-escalation of tensions.”

Millions to solve the problem of illegal immigrants

A lively debate unfolded on the problem of illegal immigration. Former US Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Julian Castro proposed to solve the problem with a new “Marshall Plan” for Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador in order to help develop the economies of these countries and reduce the flow of migrants. This idea was supported by Joe Biden, who said that $ 750 million should be allocated for these purposes, and New Jersey Senator Cory Booker proposed to save illegal immigrants from criminal prosecution. “This way we could get rid of the camps where illegal immigrants are kept and separated from their children,” he added.

At the same time, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, whose popularity in the latest polls does not exceed 0.5%, lashed out at Biden for not using his influence as vice president to in order to avoid the deportation of illegal immigrants. “Do you still think your actions are right?” – De Blasio sought a response from Biden. In response, he irritably stated that he did not intend to discuss the advice that he gave on this issue to President Barack Obama. At that moment, a banner was unfurled in the hall with the inscription “Stop the deportations from the first day” and slogans began to be chanted demanding a change in immigration policy.

Non-trivial initiatives

Very exotic proposals were also heard during the debate. For example, businessman Andrew Young proposed giving every adult American $1,000 a month to stimulate the economy, former minister Julian Castro put forward an initiative to spend $15 billion to clean up drinking water in the United States from lead pollution, and Senator Kirsten Gillibrand wondered why The US is not in a green technology race with China.

With the help of original ideas, these applicants were clearly trying to strengthen their popularity, which now, according to the results of recent polls, fluctuates within the statistical error: Corey Booker has it no more than 1.7%, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand has 0.5%, and Senator Michael Bennett – 0.2%. As a result, they may not be among the participants in the next, third televised debate, which will be held September 12-13 in Houston, Texas. By a decision of the Democratic National Committee, nominees will be required by September to secure at least two percent support in four public opinion polls and collect financial donations from at least 130,000 people.

By the end of this year, the Democratic National Committee intends to hold four more televised debates and six televised debates between January and April 2020. The cycle of TV debates will end after the start of the election campaign in February. On February 3, Iowa will host caucuses of party activists, which will elect delegates first to local Democratic party conferences, then to the state conference, and then to the national convention, which will be held July 13-16, 2020 in Milwaukee (Wisconsin).