What are high alt and ast levels. Elevated ALT and AST Levels: Causes, Diagnosis, and Management in Asymptomatic Patients

What are the primary causes of elevated ALT and AST levels. How can primary care doctors diagnose the source of enzyme elevation. What are the key steps in managing asymptomatic patients with high liver enzymes. How do liver and muscle damage contribute to increased ALT and AST.

Understanding ALT and AST: Key Liver Enzymes

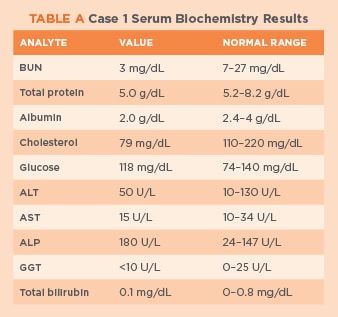

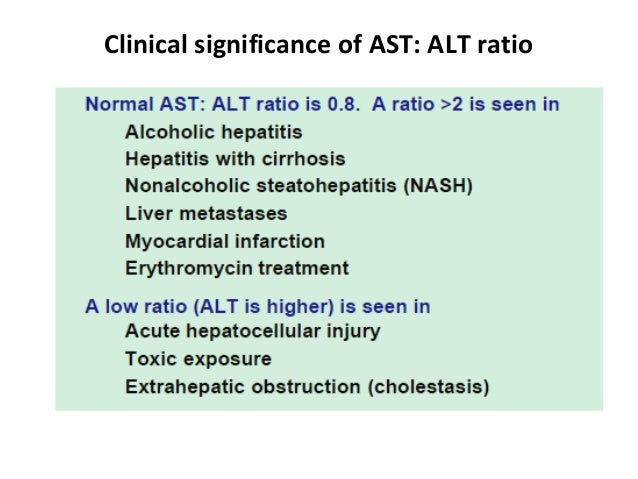

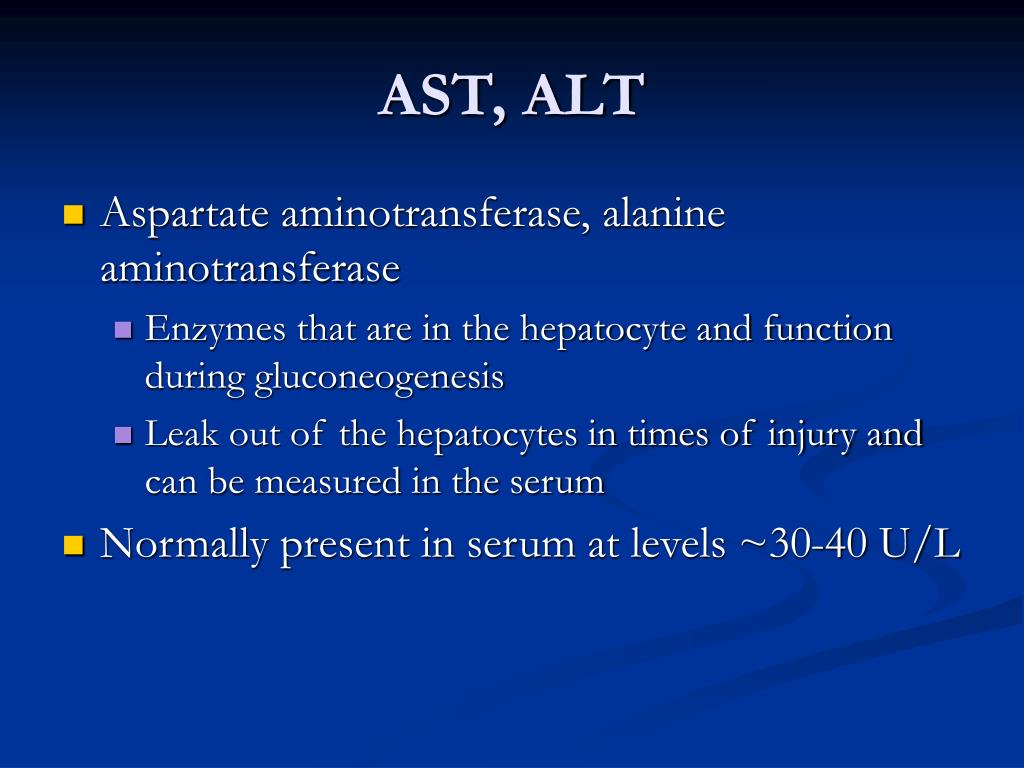

Alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) are enzymes commonly measured in routine blood tests. These enzymes play crucial roles in various bodily functions and are found in multiple organs. ALT, also known as serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), is present in the liver, heart, muscles, and kidneys. AST, also called serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT), is found in the liver, heart, muscles, kidneys, brain, pancreas, spleen, and lungs.

When cells in these organs are damaged, ALT and AST leak into the bloodstream, resulting in elevated levels on blood tests. This elevation serves as a clue for physicians to investigate potential underlying health issues. However, interpreting these results requires careful consideration and further diagnostic steps.

Common Causes of Elevated ALT and AST Levels

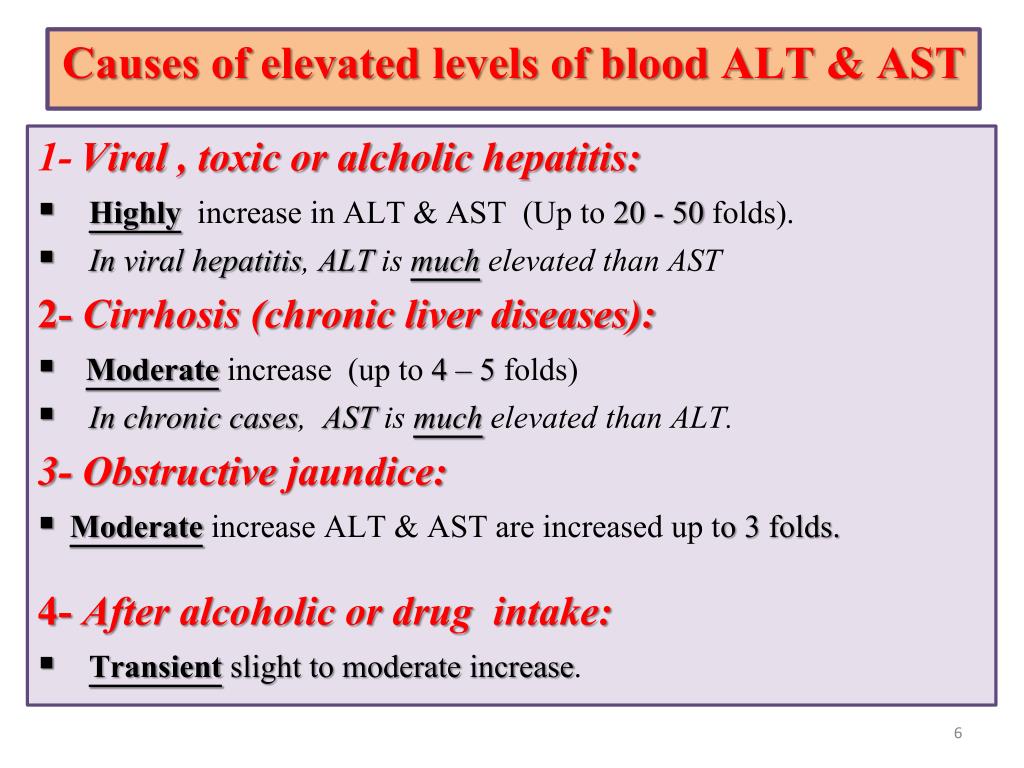

Elevated ALT and AST levels can stem from various sources, with liver and muscle damage being the most common culprits. In the general population, liver damage is more prevalent than muscle damage. Some potential causes include:

- Liver diseases (hepatitis, fatty liver disease, cirrhosis)

- Muscle disorders (inflammatory myopathies, muscular dystrophies)

- Metabolic disorders (acid maltase deficiency, debrancher enzyme deficiency)

- Medications (certain antibiotics, statins, acetaminophen)

- Alcohol consumption

- Obesity

Is it possible for both liver and muscle damage to occur simultaneously? Yes, certain metabolic muscle disorders, such as acid maltase deficiency and debrancher enzyme deficiency, can affect both liver and muscle tissues. Additionally, a person may have two separate conditions affecting these organs concurrently.

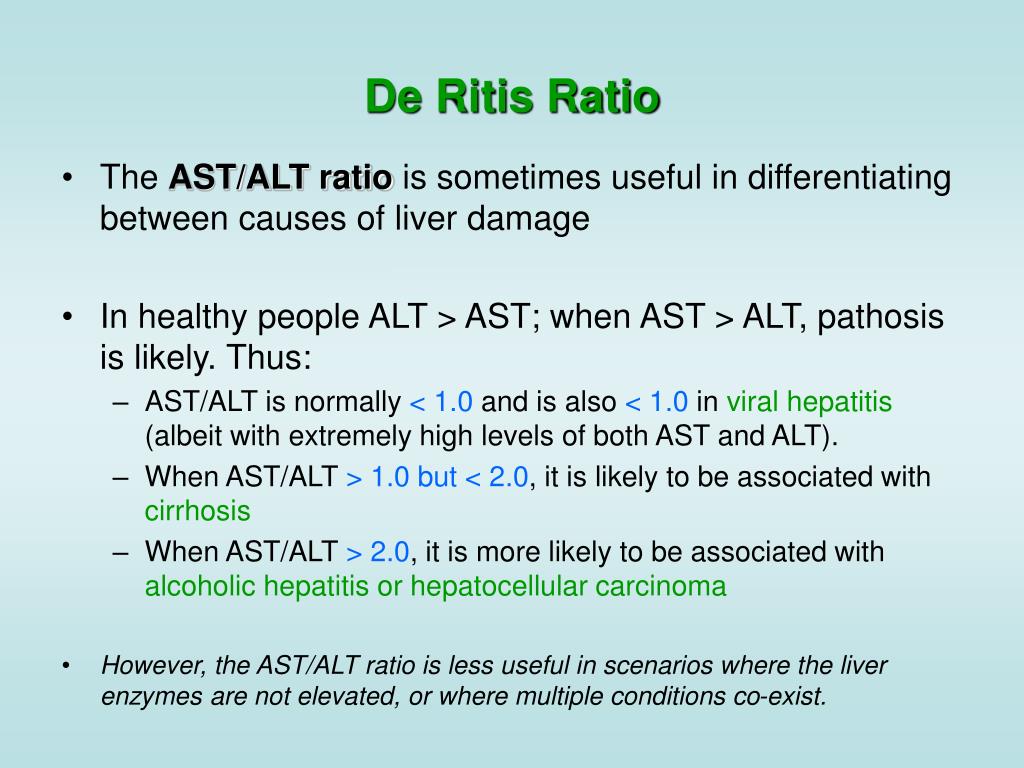

Differentiating Between Liver and Muscle Damage

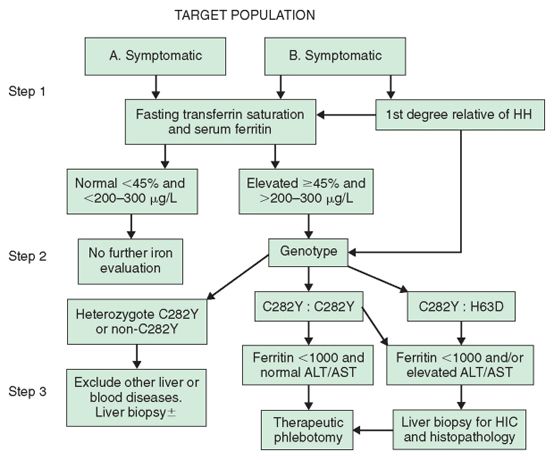

When faced with elevated ALT and AST levels in an asymptomatic patient, primary care doctors must determine the source of the enzyme elevation. This differentiation is crucial for proper diagnosis and treatment. Here are some key steps in distinguishing between liver and muscle damage:

1. Additional Enzyme Tests

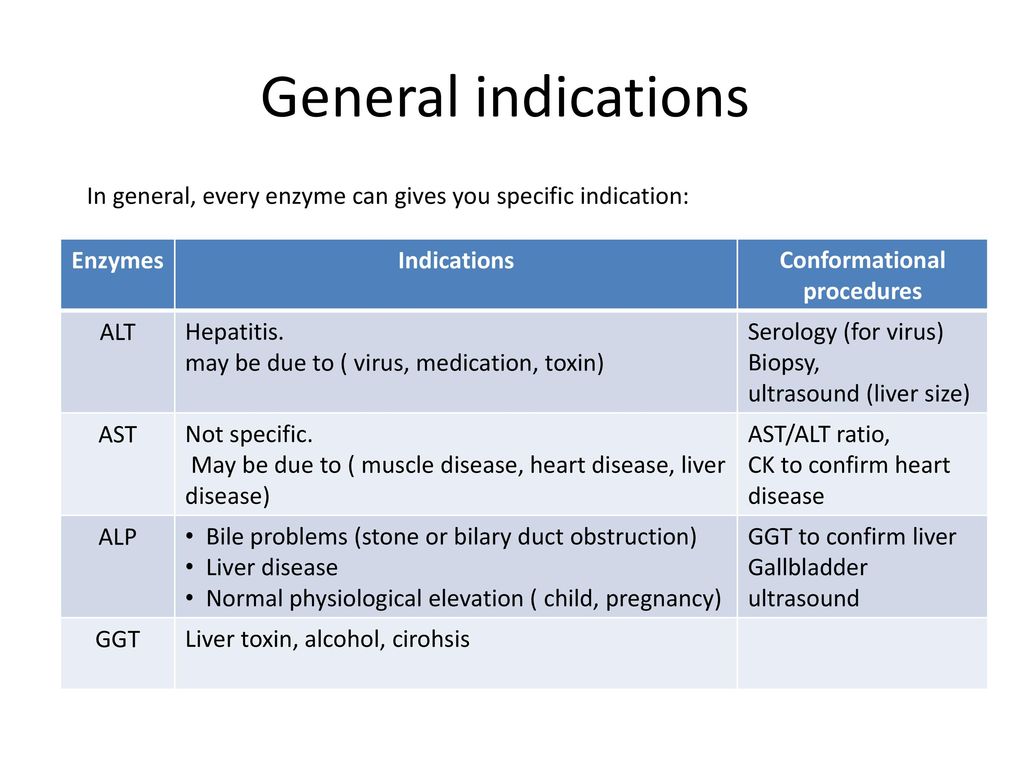

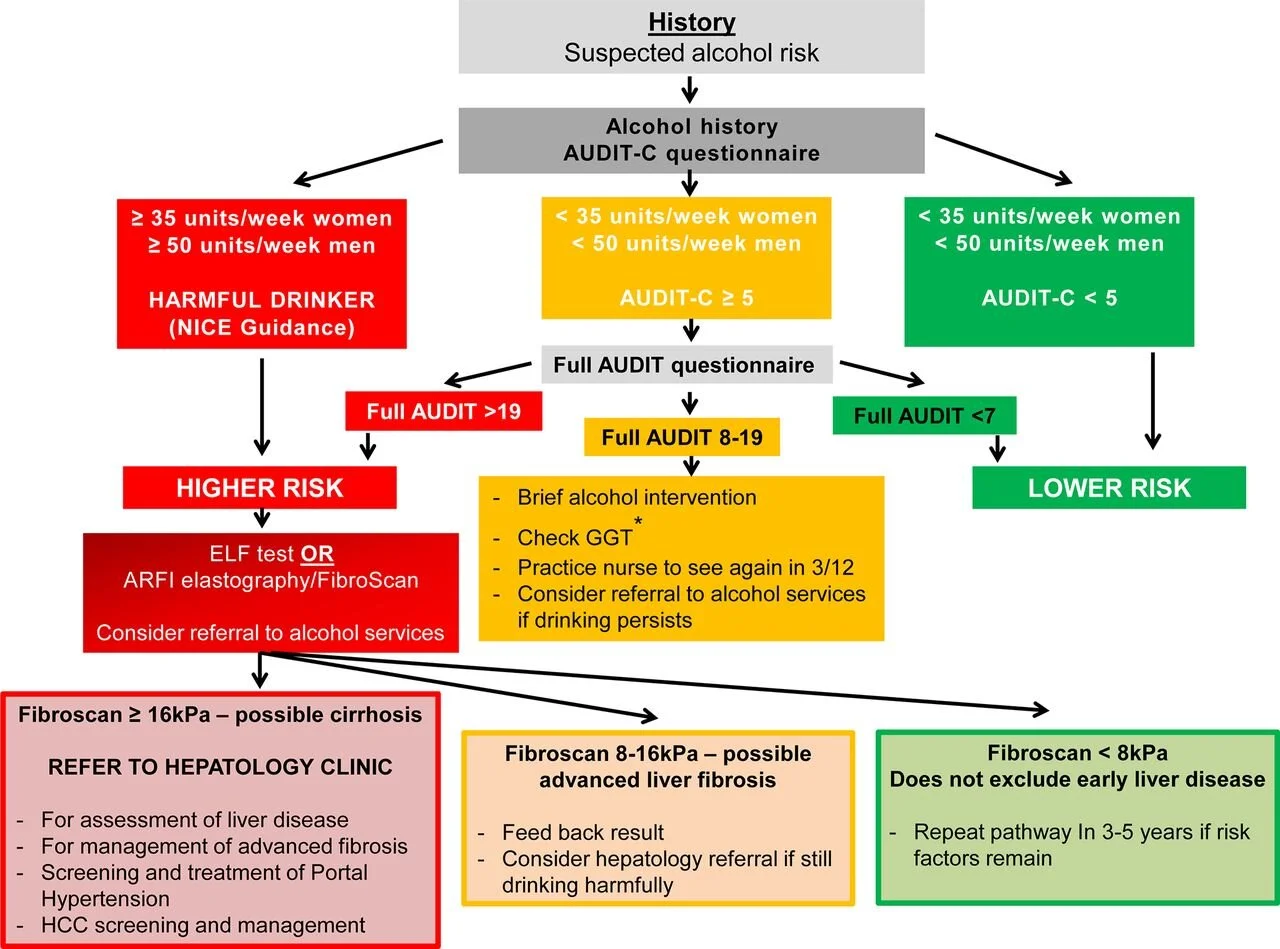

Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is an enzyme found in the liver but not in muscles. A normal GGT level with elevated ALT and AST suggests that the liver may not be the primary source of the enzyme elevation.

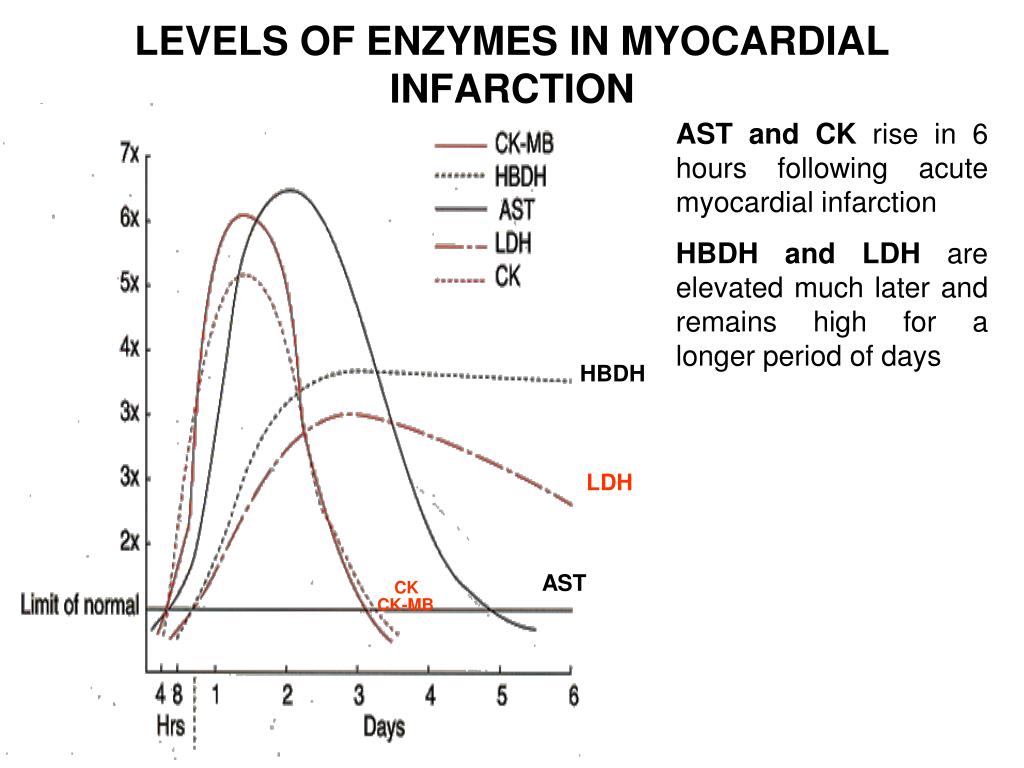

Creatine kinase (CK), also known as creatine phosphokinase (CPK), is found in the heart, skeletal muscles, and brain. The MM form of CK is specific to skeletal muscles. A high CK level alongside elevated ALT and AST points towards muscle damage as the likely cause.

2. Medical History and Risk Factors

Doctors should consider the patient’s medical history and risk factors for liver or muscle damage. Factors that may increase the risk of liver damage include:

- History of blood transfusions before 1990

- Use of hepatotoxic medications

- Recent consumption of potentially contaminated shellfish

- History of malignancy

- Recent abdominal trauma

For muscle damage, consider:

- Family history of neuromuscular disorders

- Recent intense physical activity

- Use of statins or other medications associated with muscle damage

- Symptoms of muscle weakness or pain

3. Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination can provide additional clues. Signs of liver disease may include jaundice, hepatomegaly, or spider angiomas. Muscle weakness, tenderness, or atrophy may indicate muscle damage.

Diagnostic Approach for Asymptomatic Patients with Elevated Enzymes

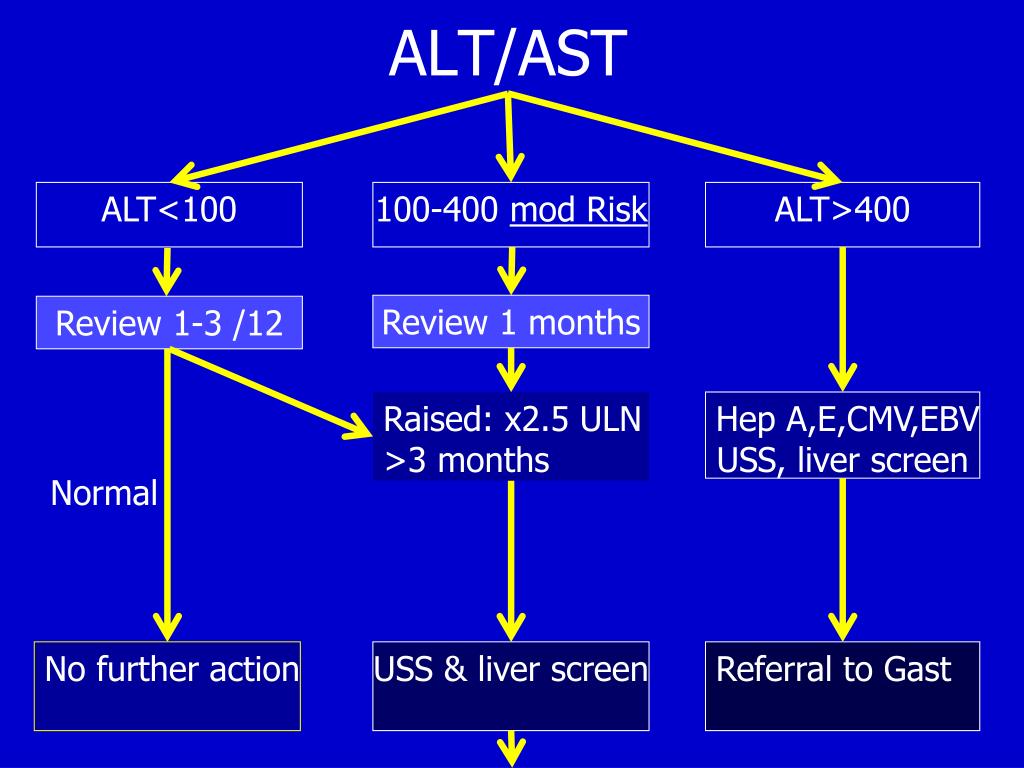

When primary care doctors encounter asymptomatic patients with elevated ALT and AST levels, a systematic diagnostic approach is essential. Here’s a step-by-step guide:

- Confirm the elevation: Repeat the blood test to ensure the results are consistent.

- Review medical history: Assess risk factors, medications, and lifestyle habits.

- Perform a physical examination: Look for signs of liver or muscle disease.

- Order additional tests: Include GGT, CK, and other liver function tests.

- Consider imaging: Ultrasound or CT scan of the liver may be necessary.

- Evaluate for metabolic syndrome: Check for obesity, diabetes, and lipid abnormalities.

- Screen for viral hepatitis: Test for hepatitis B and C.

- Assess alcohol consumption: Inquire about drinking habits and consider alcohol-related liver disease.

Management Strategies for Asymptomatic Patients

How should primary care doctors manage asymptomatic patients with elevated ALT and AST levels? The approach depends on the underlying cause and the degree of elevation. Here are some general strategies:

1. Lifestyle Modifications

Encourage patients to adopt healthy lifestyle habits, including:

- Maintaining a balanced diet

- Exercising regularly

- Limiting alcohol consumption

- Achieving a healthy weight

2. Medication Review

Evaluate the patient’s current medications and consider discontinuing or adjusting any potentially hepatotoxic drugs.

3. Treatment of Underlying Conditions

If a specific cause is identified, such as viral hepatitis or metabolic disorder, initiate appropriate treatment or referral to a specialist.

4. Monitoring and Follow-up

Schedule regular follow-up appointments to monitor enzyme levels and assess for the development of symptoms. Repeat liver function tests every 3-6 months, depending on the severity of the elevation.

5. Patient Education

Educate patients about the potential causes of elevated enzymes and the importance of adherence to lifestyle modifications and follow-up care.

When to Refer to a Specialist

In some cases, primary care doctors may need to refer patients to specialists for further evaluation and management. Consider referral in the following situations:

- Persistent elevation of enzymes despite initial management

- Suspicion of advanced liver disease or cirrhosis

- Diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis or other complex liver disorders

- Signs of muscle disease requiring neurological evaluation

- Need for liver biopsy or advanced imaging studies

Potential Complications of Untreated Elevated Enzymes

While many cases of mildly elevated ALT and AST in asymptomatic patients may not progress to serious illness, it’s crucial to monitor and address these abnormalities. Potential complications of untreated elevated enzymes include:

Liver-related Complications

- Progression of liver fibrosis to cirrhosis

- Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Liver failure in severe cases

Muscle-related Complications

- Progression of underlying neuromuscular disorders

- Increased risk of rhabdomyolysis in certain conditions

- Impaired mobility and quality of life

How can primary care doctors effectively communicate the importance of follow-up and adherence to management plans? It’s essential to educate patients about the potential long-term consequences of persistently elevated enzymes and emphasize the benefits of early intervention and lifestyle modifications.

Emerging Research and Future Directions

The field of hepatology and neuromuscular medicine continues to evolve, with ongoing research aimed at improving the diagnosis and management of patients with elevated ALT and AST levels. Some areas of current interest include:

1. Non-invasive Biomarkers

Researchers are exploring new biomarkers that can more accurately differentiate between liver and muscle damage, potentially reducing the need for invasive procedures like liver biopsies.

2. Genetic Testing

Advancements in genetic testing may help identify individuals at higher risk for certain liver or muscle disorders, allowing for earlier intervention and personalized treatment strategies.

3. Novel Therapeutic Approaches

Ongoing clinical trials are investigating new medications and treatment modalities for various liver and muscle diseases that can cause enzyme elevations.

4. Artificial Intelligence in Diagnosis

Machine learning algorithms are being developed to assist in the interpretation of complex laboratory and imaging data, potentially improving the accuracy and speed of diagnosis.

How might these advancements impact the role of primary care doctors in managing patients with elevated ALT and AST levels? As new diagnostic tools and treatments become available, primary care physicians will need to stay informed about the latest developments and work closely with specialists to provide optimal care for their patients.

The Role of Patient Engagement in Management

Effective management of elevated ALT and AST levels in asymptomatic patients requires active participation from the patients themselves. Primary care doctors play a crucial role in fostering patient engagement through various strategies:

1. Shared Decision-Making

Involve patients in the decision-making process regarding diagnostic tests, lifestyle modifications, and treatment options. This approach can increase patient buy-in and adherence to management plans.

2. Health Literacy

Provide clear, understandable information about the significance of elevated enzymes and potential health implications. Use visual aids, analogies, and plain language to explain complex medical concepts.

3. Goal Setting

Work with patients to set realistic, achievable goals for lifestyle modifications and health improvements. This can include targets for weight loss, exercise frequency, or alcohol reduction.

4. Technology Integration

Utilize digital health tools, such as smartphone apps or wearable devices, to help patients track their progress and stay motivated in their health journey.

5. Support Systems

Encourage patients to involve family members or friends in their health management. Support groups or peer mentoring programs can also provide valuable emotional and practical support.

How can primary care doctors assess and improve patient engagement in the management of elevated ALT and AST levels? Regular check-ins, motivational interviewing techniques, and the use of patient-reported outcome measures can help gauge engagement levels and identify areas for improvement.

Integrating Care Across Specialties

Managing patients with elevated ALT and AST levels often requires a multidisciplinary approach, especially when the underlying cause involves multiple organ systems. Primary care doctors can serve as the coordinators of care, ensuring seamless communication and collaboration between various specialists. This integrated approach may involve:

1. Hepatologists

For advanced liver disease management and specialized diagnostic procedures.

2. Neurologists

To evaluate and manage neuromuscular disorders that may be causing enzyme elevations.

3. Endocrinologists

For management of metabolic disorders and diabetes, which can contribute to liver enzyme abnormalities.

4. Nutritionists

To provide tailored dietary advice for patients with fatty liver disease or other metabolic conditions.

5. Mental Health Professionals

To address psychological aspects of chronic health conditions and support behavior change.

How can primary care doctors effectively coordinate care across multiple specialties? Implementing clear communication protocols, utilizing shared electronic health records, and organizing regular case conferences can facilitate better integration of care for patients with complex health needs.

In conclusion, the management of elevated ALT and AST levels in asymptomatic patients requires a comprehensive approach that combines careful diagnostic evaluation, individualized treatment strategies, and ongoing monitoring. By staying informed about the latest developments in hepatology and neuromuscular medicine, fostering patient engagement, and coordinating care across specialties, primary care doctors can play a pivotal role in improving outcomes for these patients. As research continues to advance our understanding of liver and muscle disorders, the future holds promise for more precise and effective management strategies, ultimately leading to better health outcomes for patients with elevated enzyme levels.

Simply Stated: Elevated Enzymes – Quest

Elevated enzymes are a frequently encountered problem in general medical practice, but their meaning often isn’t so simple to discern. When they’re found with a neuromuscular disease, the situation can get complicated.

What’s an enzyme?

There are thousands of enzymes in the cells in our bodies, where they act as catalysts for all the chemical reactions that take place in these cells. Without them, these reactions either wouldn’t occur or would be too slow for the cells’ needs.

Many enzymes are normally present in the blood and can be measured there. When cells are damaged by disease or injury, large amounts of these leak out, causing blood tests to show that enzymes are elevated above normal. (You can roughly compare this situation to a car that’s leaking oil. Leaks in many parts of the engine can have the same result: oil all over your driveway.)

Where did it come from?

Measuring enzymes is only a clue to a possible diagnosis or problem, not a diagnosis in itself. An elevated enzyme level on a screening test should prompt a physician to look further into which areas of the body may be leaking enzymes into the blood, just as a good mechanic looks for the source of a car’s oil leak. (In either case, finding the source is only the first step. The next steps are finding out why the leak has occurred and attempting to fix it.)

An elevated enzyme level on a screening test should prompt a physician to look further into which areas of the body may be leaking enzymes into the blood, just as a good mechanic looks for the source of a car’s oil leak. (In either case, finding the source is only the first step. The next steps are finding out why the leak has occurred and attempting to fix it.)

Two enzymes often measured on routine tests are known as ALT (alanine transaminase) and AST (aspartate transaminase). ALT is found in the liver, heart, muscles and kidneys. AST is in the liver, heart, muscles, kidneys, brain, pancreas, spleen and lungs. ALT is also known as SGPT (serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase), and AST is also called SGOT (serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase).

In many neuromuscular disorders, muscle tissue is gradually damaged, either by an attack from the immune system (as in inflammatory myopathies), or by a genetic mutation inside the cells (as in the muscular dystrophies). When routine tests measuring ALT or AST are performed in people with neuromuscular disorders, these enzymes are often elevated in the blood, because the ALT and AST are leaking out of damaged muscles. But they can also leak out of other organs, particularly the liver.

But they can also leak out of other organs, particularly the liver.

Liver or muscle?

If a neuromuscular disorder hasn’t yet been diagnosed, a doctor may be misled into thinking that a damaged liver, not damaged muscles, is the source of the enzyme leak. In the general population, liver damage is more common than muscle damage, so this assumption isn’t too surprising.

The careful physician will, however, investigate further. An enzyme called GGT or gamma-GT (gamma-glutamyltransferase, also gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase) is found in the liver but not in the muscles. If it’s unclear whether the liver is damaged, a normal GGT level can help a doctor decide that it’s not, while a high GGT level would sway him or her toward thinking it is. (That’s far from the only test that can be done, but it’s an easy and relatively inexpensive one.)

CK (creatine kinase), also called CPK (creatine phosphokinase), is only found in the heart, skeletal muscles and brain. The MM form of CK is the type found in skeletal muscles, and it can be specifically measured when a doctor suspects a muscle problem. A normal CK level with elevated ALT and AST enzymes would sway a doctor toward thinking there’s a liver problem; a high CK with high ALT and AST levels suggests that something’s going on in the muscle.

A normal CK level with elevated ALT and AST enzymes would sway a doctor toward thinking there’s a liver problem; a high CK with high ALT and AST levels suggests that something’s going on in the muscle.

So, doing additional enzyme tests after a general screen can help a doctor decide whether the high ALT and AST are more likely the result of liver or muscle damage.

Of course, there could be a problem in both liver and muscle. (Your 1982 Volvo could be leaking oil from both the oil pan and a gasket.) Some metabolic muscle disorders, such as acid maltase deficiency and debrancher enzyme deficiency, affect both tissues. And two diseases can occur in the same person.

What damages the liver?

A person at high risk for hepatitis or other liver damage, whether or not he or she has a neuromuscular disease, needs further attention focused on the liver, with the medical history and physical exam taken into account. Liver problems may occur in someone who’s had blood transfusions before 1990 (before modern hepatitis virus testing), taken drugs (prescription, over-the-counter or recreational) that are known to damage the liver, recently eaten potentially contaminated shellfish, had a history of malignancy or recently been stabbed in the abdomen — whether there’s a neuromuscular disease or not.

The medications riluzole, used to treat amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and methotrexate, used to treat inflammatory myopathies and myasthenia gravis, are among the many drugs that have liver-damaging potential.

Most of the time, elevated ALT and AST levels in people with degenerating muscles don’t mean much, other than that these enzymes, along with CK, are leaking out of the muscles. (The high levels of enzymes do no harm in and of themselves.) But sometimes, depending on results of other tests and the person’s history, they can mean there’s trouble in the liver or even in another organ. That’s where medical detective work is needed.

Serum enzyme levels of CK, LDH, ALT and AST are the most widely measured enzymes in patients suspected of having a muscle disease. However, it should be noted that the deficiency of a specific enzyme can also be the underlying cause of a muscle disease. For instance, people with metabolic myopathies lack certain enzymes involved in providing energy that help muscles contract. The affected muscles can’t function normally leading to symptoms like progressive muscle weakness, exercise intolerance and even heart problems. Different forms of metabolic myopathies are distinguished by which enzyme is deficient or missing. Examples of diseases associated with reduced levels of specific enzymes include Pompe disease which is caused by acid maltase deficiency; and McArdle disease which is due to a lack of enzyme that assist in carbohydrate metabolism. For more information on enzyme-deficient metabolic myopathies see: (https://www.mda.org/disease/metabolic-myopathies/types)

The affected muscles can’t function normally leading to symptoms like progressive muscle weakness, exercise intolerance and even heart problems. Different forms of metabolic myopathies are distinguished by which enzyme is deficient or missing. Examples of diseases associated with reduced levels of specific enzymes include Pompe disease which is caused by acid maltase deficiency; and McArdle disease which is due to a lack of enzyme that assist in carbohydrate metabolism. For more information on enzyme-deficient metabolic myopathies see: (https://www.mda.org/disease/metabolic-myopathies/types)

“Simply Stated” is a Quest column designed to explain some terms and basic facts about neuromuscular diseases.

Disclaimer: No content on this site should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.

What medications cause liver enzymes to be elevated?

Medically reviewed by Sally Chao, MD. Last updated on March 7, 2022.

Many medications can cause liver enzymes to be elevated.

A familiar over-the-counter medication that can cause liver damage from an overdose is acetaminophen (Tylenol). A healthy person should not take more than 3,000 to 4,000 milligrams in a single day. This maximum dose range may not be safe if you drink alcohol or have liver disease.

Another class of medications that sometimes causes liver enzymes to rise are cholesterol lowering medications, called statins. Statins include the medications simvastatin, atorvastatin, pravastatin and lovastatin. Statins rarely cause liver damage, and doctors no longer check liver enzymes for people on statins routinely.

Other common medications that may cause elevated liver enzymes include:

- The antibiotics synthetic penicillin, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline

- The anti-seizure drugs carbamazepine and phenytoin and valproic acid

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- The diabetes drugs sulfonylureas and glipizide

- The tuberculosis drugs isoniazid, pyrazinamide and rifampin

- The antifungal drug ketoconazole

- The antidepressant fluoxetine

- The antipsychotic risperidone

- The antiviral drugs valacyclovir and ritonavir

- The rheumatoid arthritis drug methotrexate

- Abused drugs such as alcohol, cocaine and anabolic steroids

- The herbal medications chaparral, comfrey tea, kava, skullcap, yohimbe, ji bu huan and ephedra

As part of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval process, medications are screened for their potential to cause liver damage. In most cases, you will not get liver damage if you take these drugs as prescribed. Damage may occur if you are sensitive to the drug, if you take more than prescribed or if you already have a liver condition.

In most cases, you will not get liver damage if you take these drugs as prescribed. Damage may occur if you are sensitive to the drug, if you take more than prescribed or if you already have a liver condition.

Herbal medications are not tested by the FDA. If you have liver disease, check with your doctor before taking any new medications or supplements.

Liver enzymes

Liver enzymes are proteins your liver uses for normal liver functions. When your liver is damaged, these enzymes leak out into your blood and can be measured with blood testing called liver function testing.

There are several liver enzymes, but the ones that show liver damage from medications are aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT). Medications may cause liver enzymes to be elevated without serious liver damage until they reach 3 to 5 times the normal levels.

References

- U.S. National Library of Medicine Bookshelf. Liver Function Tests. StatPearls. August 2021.

Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482489/. [Accessed February 4, 2022].

Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482489/. [Accessed February 4, 2022]. - Johnson & Johnson. Tylenol Dosage for Adults. Available at: https://www.tylenol.com/safety-dosing/dosage-for-adults. [Accessed February 9, 2022].

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Drug Safety Communication: Prescription Acetaminophen Products to be Limited to 325 mg Per Dosage Unit; Boxed Warning Will Highlight Potential for Severe Liver Failure. February 7, 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-prescription-acetaminophen-products-be-limited-325-mg-dosage-unit. [Accessed February 9, 2022].

- American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). Medications and the Liver. December 2012. Available at: https://gi.org/topics/medications-and-the-liver/. [Accessed February 4, 2022].

- Malakouti M, Kataria A, Ali SK, Schenker S. Elevated Liver Enzymes in Asymptomatic Patients — What Should I Do? J Clin Transl Hepatol.

2017 Dec 28;5(4):394-403. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5719197/.

2017 Dec 28;5(4):394-403. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5719197/.

Related medical questions

- What’s the best sore throat medicine to use?

- Which painkiller should you use?

- What is paracetamol / panadol called in the US?

- Acetaminophen vs Ibuprofen: Which is better?

- How long does Percocet stay in your system?

- Can you take tramadol with acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or aspirin?

- Advil (ibuprofen) & Tylenol (acetaminophen) together, is it safe?

- Is it safe to take acetaminophen every day?

- How long does it take for Tylenol to start working?

- Is acetaminophen the same as Tylenol?

- Is Tylenol (acetaminophen) a blood thinner?

Drug information

- Acetaminophen Information for Consumers

- Acetaminophen Information for Healthcare Professionals

(includes dosage details) - Side Effects of Acetaminophen

(detailed)

Related support groups

- Acetaminophen

(148 questions, 213 members)

Medical Disclaimer

prices, preparation – Kinzersky Clinic

Description

Professor Kinzersky’s clinic offers blood tests for ALT and AST. Our diagnostic center has a wide range of possibilities for diagnosing diseases. The clinic works according to European standards, the clinic’s specialists use the latest equipment and methods for the effective treatment and diagnosis of diseases. To make an appointment with a physiotherapist, call +7 (351) 200-40-60 or fill out the form on the website.

Our diagnostic center has a wide range of possibilities for diagnosing diseases. The clinic works according to European standards, the clinic’s specialists use the latest equipment and methods for the effective treatment and diagnosis of diseases. To make an appointment with a physiotherapist, call +7 (351) 200-40-60 or fill out the form on the website.

Preparing for tests

It is recommended to donate blood before a biochemical study on an empty stomach (the last meal should be no earlier than 10-12 hours before). For 2-3 days before the analysis, a sparing diet should be followed. On the eve, you should not drink coffee and strong tea.

In addition, physical activity, stress and medication should be avoided the day before the test.

How to get tested

Procedure duration:

5 minutes

Preparation of results:

1-2 days

Research result:

ALT (alanine aminotransferase) and AST (aspartate aminotransferase) blood test shows the level of these enzymes in the blood. High levels of ALT and AST can indicate damage to cells in the liver, heart, or other organs.

High levels of ALT and AST can indicate damage to cells in the liver, heart, or other organs.

Price of blood test for ALT and AST

Reviews

All reviews

Excellent clinic.

Competently, professionally, although a little expensive, thanks to the specialists for giving explanations

The best clinic, both I and my mother go. Very satisfied, always treated like a human being

Very neat and clean.

I like colored plastic chairs, bright colors are pleasing to the eye.

The staff is friendly. The quality of services is high, in no comparison with free medicine, which cannot diagnose correctly.

There is a coffee shop in the same room, which is very convenient.

Making an appointment

Enter name

Enter telephone *

Enter the date of receipt

Enter e-mail

By clicking the “Make an appointment” button, you agree

to the terms of personal data processing

Making an appointment

Enter name

Enter telephone *

Enter the date of receipt

Enter e-mail

By clicking the “Make an appointment” button, you agree

with the conditions for processing personal data

The site is under construction. Information may not be correct. All information can be clarified by tel. 8 (351) 200-40-60 and 8 (351) 225-40-60

Information may not be correct. All information can be clarified by tel. 8 (351) 200-40-60 and 8 (351) 225-40-60

An increase in ALT with HIV/HBV coinfection may indicate NAFLD

According to a study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, a persistent increase in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in people with HIV and hepatitis B, even despite control of HBV viral load, indicates the need to assess the metabolic risk of developing fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Using data from a multicentre, prospective cohort study of adults with HIV/HBV coinfection on antiretroviral therapy, we attempted to determine the presence of concomitant fatty liver disease (NAFLD), its activity, and clinical correlates, including cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. In addition, they evaluated the effect of fatty liver disease on tests (ALT and aspartate aminotransferase [AST]) as an adverse reaction of liver activity over time.

Study participants who were positive for anti-HIV and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for at least 6 months were followed up at 8 sites in the Hepatitis B Research Network in the US and Canada. From April 28, 2014 to November 7, 2018, 114 patients underwent liver biopsy. All of them were followed up for an average of 3 years. Steatohepatitis was a consequence of the presence of steatosis, ballooning and perisinusoidal fibrosis. Fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was defined as ≥5% steatosis and/or steatohepatitis.

From April 28, 2014 to November 7, 2018, 114 patients underwent liver biopsy. All of them were followed up for an average of 3 years. Steatohepatitis was a consequence of the presence of steatosis, ballooning and perisinusoidal fibrosis. Fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was defined as ≥5% steatosis and/or steatohepatitis.

The mean age of participants was 49 years, 93% were male, 51.3% were black, 92.3% had HIV RNA <400 copies/mL, and 83% had HBV DNA <1000 IU/mL. Of the 114 participants, 11 (9.7%) had steatohepatitis and 23 (20.2%) had steatosis. A higher percentage of participants with at least twice normal ALT levels and abnormal AST levels had fatty liver disease. Half of the participants with steatohepatitis had at least twice the normal ALT (versus 17.4% with steatosis and 7.8% without fatty liver disease), and abnormal AST was observed in 60% of patients with steatohepatitis compared with 30, 4% in patients with steatosis and 15.6% in patients with steatosis without fatty liver disease. NAFLD was more common in patients with a higher degree of inflammation, as measured by the histological activity index, and in patients with a higher degree of perisinusoidal fibrosis; however, there was no significant difference in the Ishak Fibrosis Score between the NAFLD groups.

NAFLD was more common in patients with a higher degree of inflammation, as measured by the histological activity index, and in patients with a higher degree of perisinusoidal fibrosis; however, there was no significant difference in the Ishak Fibrosis Score between the NAFLD groups.

Compared with participants without fatty liver disease, participants with NAFLD had higher levels of insulin (mean 19 vs 8.5 mcg/mL; P<0.001), glucose (median 94 vs 89 mg/dL; P=0 12), and fatty acid levels (median 0.49 vs. 0.39 mg/dl; P = 0.21).

While traditional lipid profiles, including total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), did not differ significantly among people with and without fatty liver disease, participants with NAFLD had significantly higher median levels of triglycerides (171 vs. 100.5 mg/dl, P<0.001) and apolipoprotein B (95.5 vs 80.5 mg/dl, P=0.028) compared to the non-NAFLD group. In addition, patients with fatty liver disease had a significantly higher concentration of LDL particles, a low density of LDL-C, and a low concentration of the lower subclass HDL 2-C (P ≤. 001).

001).

After adjusting for age, sex, and alcohol consumption, whites and other races versus blacks (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 8.49 and 16.54 respectively; P = 0.0004), higher ALT (aOR, 3, 13 per doubling of ALT; P = 0.003), hypertension (aOR, 10.93; P = 0.002), hyperlipidemia (aOR, 4.36; P = 0.04) and family history of diabetes (aOR, 5.38; P = 0.02) were independently associated with higher odds of NAFLD.

After adjusting for HBV DNA, age, and sex, compared with the non-NAFLD group, the presence of steatohepatitis was associated with a 1.93 (95% CI, 1.37–2.72) times increased risk of having ALT levels higher, whereas steatosis without steatohepatitis was associated with a 1.34-fold (95% CI, 1.05–1.70) risk of having ALT abnormal (P<0.001).

Limitations of this study included self-selection of participants seeking liver biopsy, which limited generalization to the entire HIV/HBV population. In addition, although ALT levels were higher in NAFLD in the study cross-section, and this relationship persisted over time when HBV viral levels were controlled, the investigators were unable to determine whether ALT increased at the onset of fatty liver disease.

Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482489/. [Accessed February 4, 2022].

Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482489/. [Accessed February 4, 2022]. 2017 Dec 28;5(4):394-403. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5719197/.

2017 Dec 28;5(4):394-403. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5719197/.